INTRODUCTION

As with all research projects, there have been so many zigzags in this story, it’s only reasonable to take a break to take stock of where we are in solving the puzzle of Pnina’s identity. We haven’t solved all the mysteries yet, but we know so much more now than we started with a few years ago.

Pnina Gutman is in her 70s and lives in Israel. She leads a normal life as a mother, a grandmother, and a great grandmother, but she has an unusual story. Pnina was smuggled from the Warsaw Ghetto in late 1942 when she was an infant and hidden on the Aryan side by Charlotte Rebhun, a Christian woman from Berlin. Although Pnina’s life was saved, her identity was lost. She has spent many years trying to recover it.”

I became acquainted with Pnina in 2012 when I started a pilot project through 23andMe to DNA test child survivors of the Holocaust, hoping to reunite them with otherwise unfindable family members. My source of candidates was the Missing Identity website hosted by Eva Floersheim from Norway that features compelling profiles of Holocaust survivor children who have lost their identities. The survival rate for children during the Holocaust was the lowest of all age categories. Of the 1 million Jewish children in Poland on the eve of the Holocaust, only about 5,000 survived – about one half of a percent – Pnina was one of the lucky ones.

Since the start of our project, our research group has grown, and we have consulted with major repositories of Holocaust material and civil and military records in Germany, Poland, Israel and the U.S.:

Jewish and Holocaust-Related Resources:

Yad Vashem, JRI Poland, jewishgen.org, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), International Tracing Service (ITS), William Bremen Jewish Heritage Museum, Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum, Pawiak Prison Museum,

German Civil, Historical, and Military Repositories:

Berlin Landesarchiv, Berlin Bundesarchiv Lichterfelde, Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin (ZLB), Deutsche Dienstelle, Landkreis Barnim, Badische Landesbibliotek Wurttemberg, Stadtarchiv Leipzig

Polish Civil, Historical, and Military Repositories:

Jewish Historical Institute, Polish State Archives in Warsaw, Central Archives of Modern Records in Warsaw, Archives of New Records in Warsaw, Institute of National Remembrance

U.S. Civil, Historical, and Military Repositories:

U.S. Library of Congress, U.S. National Archives

A Few of Many Websites:

Collection of historical European city and business directories – genealogyindexer.org

Victims of the Oppression under German Occupation – www.straty.pl/index.php/en/

Museum of the Warsaw Uprising biographies – www.1944.pl/powstancze-biogramy.html

Warsaw Ghetto database – warszawa.getto.pl/index.php?show=instrukcja&lang=en

Więżniowie Pawiaka (Pawiak Prisoners) – www.stankiewicze.com/pawiak/nazp3.htm

We have a great group of researchers located in all the right places:

Hania Allen Scotland

Cate Bloomquist Minnesota

Colleen Fitzpatrick, PhD California

Eva Floersheim Moss, Norway

Franek Grabowski Warsaw, Poland

Pnina Gutman Israel

Sharon M Levy Israel

THE STORY OF PNINA’S RESCUE

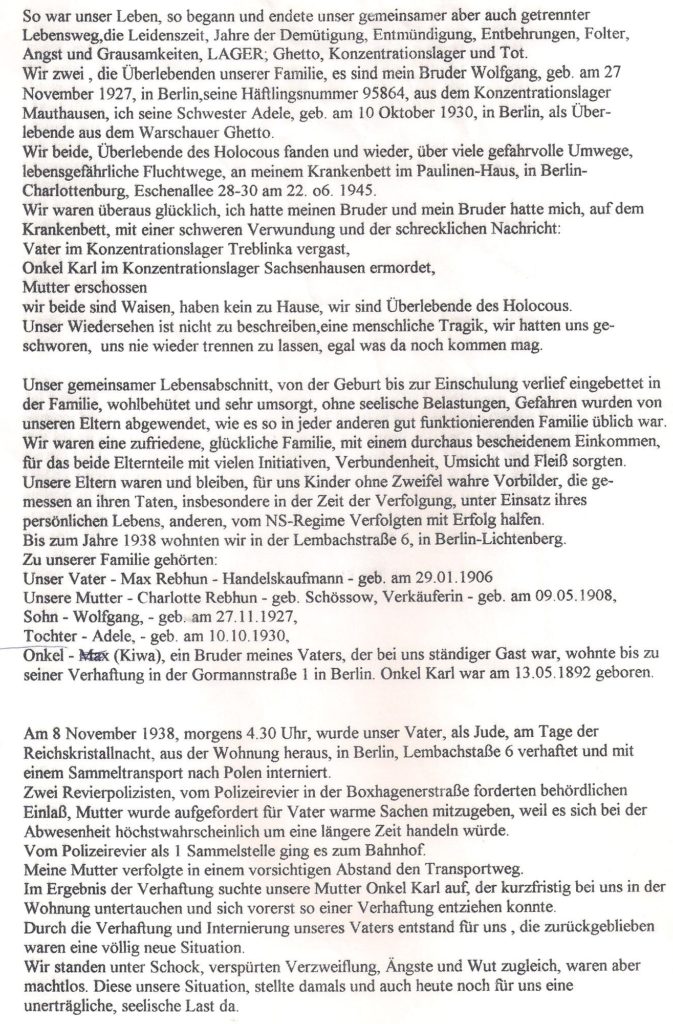

By 2012, Pnina had already discovered that being smuggled from the Warsaw Ghetto was only part of her incredible story. She had been rescued three times. In 1944, after staying with the Rebun family for about two years, she was separated from them during a selection on the outskirts of Warsaw. Charlotte’s son Wolfgang was sent to Mathausen; Charlotte and her daughter Adele were sent to a work camp. Pnina was found alone in a train station in Milanowek near Warsaw by a Red Cross worker who brought her to Franciszek Kaczmarek and his wife Stanislawa. They took Pnina in although they already had five children of their own.

After the war, when the Kaczmareks wanted to adopt Pnina, they wrote to the Jewish Central Committee (JCC) to find out whether any of her family had survived. Instead of replying, the JCC sent an emissary to the Kaczmarek’s house who took Pnina away by force, insisting she be raised a Jew. She was placed in the Otwock Orphanage, where she was adopted by the Himels. She lived with them in Lodz until the family emigrated to Israel in 1950.

Pnina’s own research had led her back to the day she was smuggled from the Ghetto. By the time I was introduced to her, she had been reunited with both the Kaczmarek and Rebhun families. Franciszek Kaczmarek and his wife were dead; Charlotte had been murdered when she returned to Berlin in 1945. The Kaczmarek children were still alive, as were Wolfgang and Adele. They had provided her with many details of her rescue. They also gave her baby pictures – some dated back to shortly after she was smuggled from the Ghetto. Two of them showed Charlotte near the park on Aleja Krolewska in Warsaw, including one with the white baby carriage she arrived in at Charlotte’s apartment, perhaps only days earlier.

Pnina with Adele and Wolfgang at the Yad Vashem ceremony naming Charlotte as Righteous before the Nations, 1998.</strong/

Because they risked their lives to save Pnina, both Charlotte Rebhun and the Kazmareks were named Righteous before the Nations by the State of Israel.

Adele and Wolfgang’s eye-witness account of Pnina’s arrival at their family apartment on Krochmalna St. introduced several new characters to her story: Gertrude Spiro and her daughter Sonia, along with an unnamed German soldier. According to the Rebhuns:

Just before the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Wolfgang recalled, a young Jewish couple, possibly freedom fighters, had convinced a German soldier to smuggle their daughter out of the ghetto. The nine-month-old had arrived in a white baby carriage, with a note draped around her neck reading Barbara Wenglinski. The soldier’s girlfriend, Sonia Spyra, passed the baby on to Charlotta Rebhun, Wolfgang’s mother, to be hidden in the Arian [sic] part of Warsaw.

Their testimony to the Yad Vashem adds a few details:

It all started with a conversation between Mrs. Gertrude Spyra, wife of a Jew from Berlin, and my mother, Charlotte Rebhun born Schössow.

The conversation involved the adoption of a small child of a Jewish family from the Warsaw ghetto – the safekeeping and the survival of the child until its retrieval after surviving threats to life and limb. The birth parents were organized resistance fighters in the Warsaw ghetto.

The handover of Baschke by the birth mother took place in our former apartment in Warsaw Krochmalna No. 33, and included a baby stroller with baby clothing.

The intention was presented to my mother, that after taking care of their responsibilities in the Ghetto, the parents would return for the child after not too long a period of time.

After that, in the fall of 1942 – the exact time unfortunately, does not come to mind – there was no sign of the parents. Barbara’s parents were Polish Jews.

GERTRUDE PRIESS-SPIRO

Gertrude Spiro was the person who organized Pnina’s rescue, yet the Rebhuns had little information about her and her daughter Sonia. They did not even know how to spell their last name. Now, thanks to records we’ve located at the Berlin Bundesarchiv Lichterfelde, the Berlin Landesarchiv, and through the Pawiak Prison Museum in Warsaw, we know so much more. We hope that by researching the Spiros, we might find clues to Pnina’s identity. It is even possible, although unlikely, that Sonia Spiro may still be alive. Recent discoveries have also brought us closer to identifying the German soldier who was the go-between with Pnina’s parents.

Gertrude Priess was born in Bladiau, Kreis Heiligenbeil, East Prussia on 24 February 1899, the daughter of Friedrich Priess and Maria born Brockmann (Bruchmann). The Priess family moved to Berlin about 1912 where they lived at 176/177 Brunnenstrasse until at least 1942. Their residence was located in what became East Berlin, three blocks from where the Berlin Wall once divided the city.

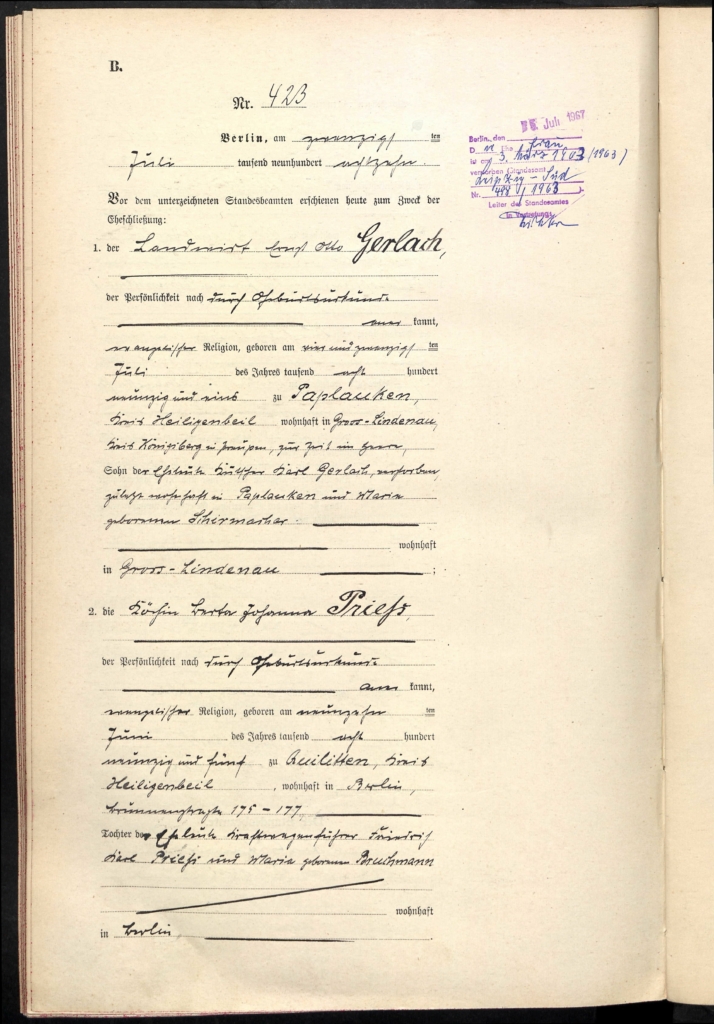

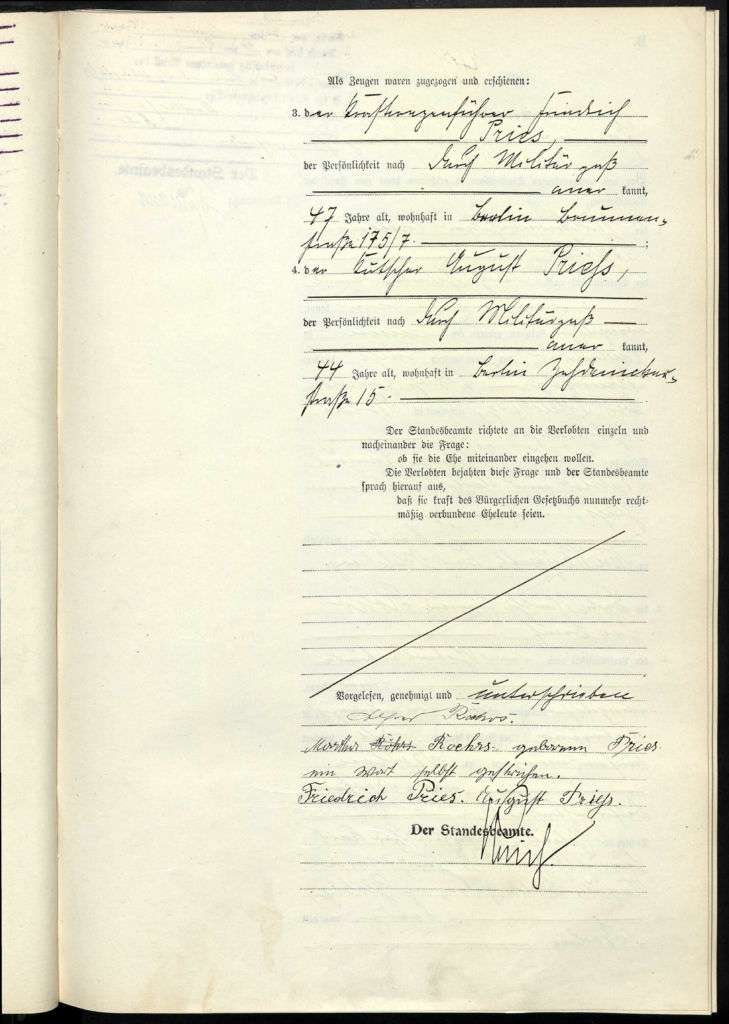

According to marriage records held by the Berlin Landesarchiv, Gertrude had two sisters:

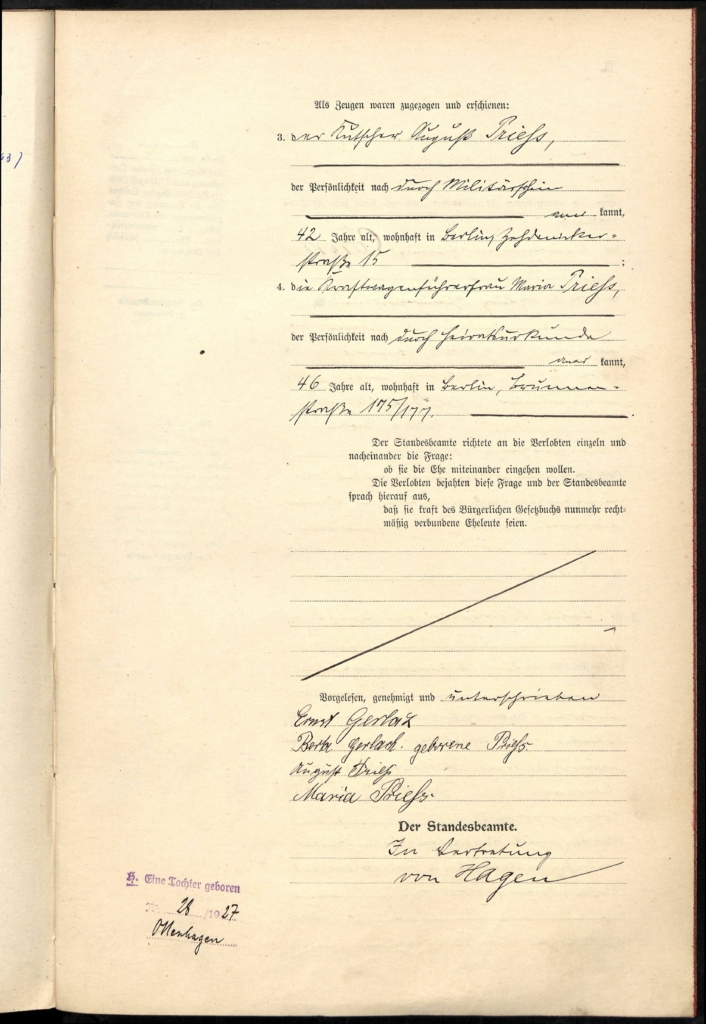

Berta Johanna Priess, b 19 June 1895 in Quilitten, Kreis Heiligenbeil, East Prussia. She was a cook. Berta married Ernst Otto Gerlach on 20 July 1918 in Berlin. Ernst was born 24 Jul 1891 in Paplauken, Kreis Heiligenbeil, just a few miles away from where Berta was born four years later. At the time of their marriage, Ernst was a farmer living in Gross Lindenau, Kreis Konigsburg, East Prussia. According to notes included on their marriage certificate, the couple had a daughter, name unknown, b 1927 in Ottenhagen, Kreis Heiligenbeil, East Prussia, and Berta died 3 March 1963 in Leipzig.

Berta Johanna Priess, b 19 June 1895 in Quilitten, Kreis Heiligenbeil, East Prussia. She was a cook. Berta married Ernst Otto Gerlach on 20 July 1918 in Berlin. Ernst was born 24 Jul 1891 in Paplauken, Kreis Heiligenbeil, just a few miles away from where Berta was born four years later. At the time of their marriage, Ernst was a farmer living in Gross Lindenau, Kreis Konigsburg, East Prussia. According to notes included on their marriage certificate, the couple had a daughter, name unknown, b 1927 in Ottenhagen, Kreis Heiligenbeil, East Prussia, and Berta died 3 March 1963 in Leipzig.

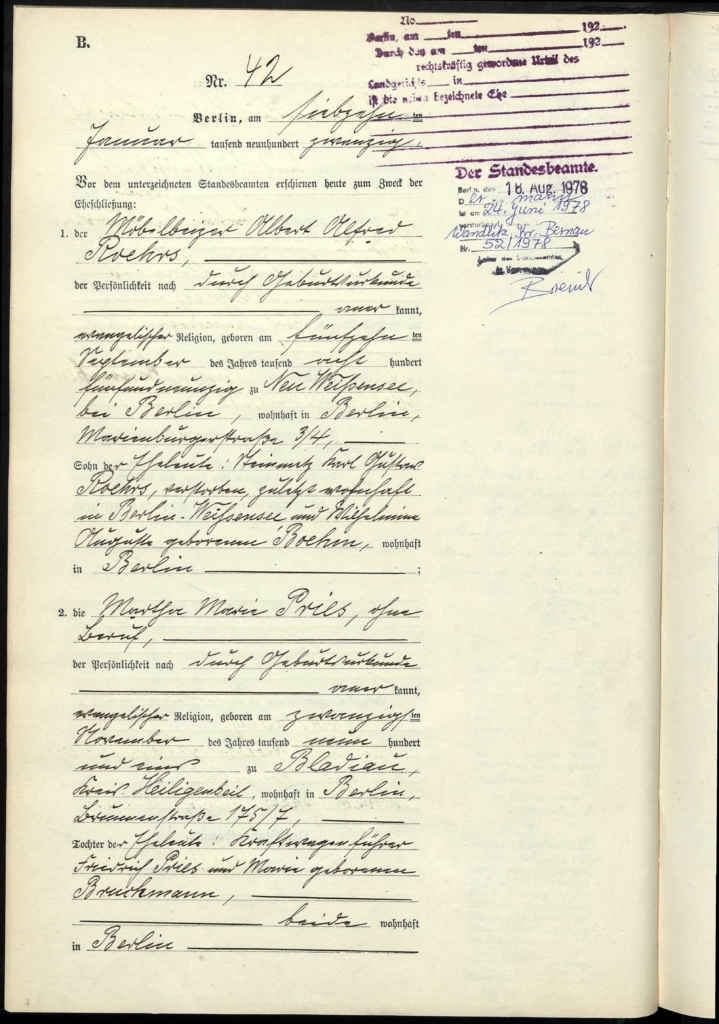

Martha Maria Priess, b 20 Nov 1901 in Bladiau, Kreis Heiligenbeil, East Prussia. She was unemployed when she married Albert Alfred Roehrs on 17 Jun 1920 in Berlin. Alfred was born on 15 September 1895 in Neu Weissensee near Berlin. He varnished furniture for a living, and later owned a flower shop in Berlin. At the time of their

marriage, Alfred lived on Anklamer St, about two blocks away from the Priess residence at 175-177 Brunnenstrasse in Berlin. They had no known children. A note on their marriage certificate indicates that Alfred died 24 Jun 1978 in Wandlitz, Kreis Bernau.

marriage, Alfred lived on Anklamer St, about two blocks away from the Priess residence at 175-177 Brunnenstrasse in Berlin. They had no known children. A note on their marriage certificate indicates that Alfred died 24 Jun 1978 in Wandlitz, Kreis Bernau.

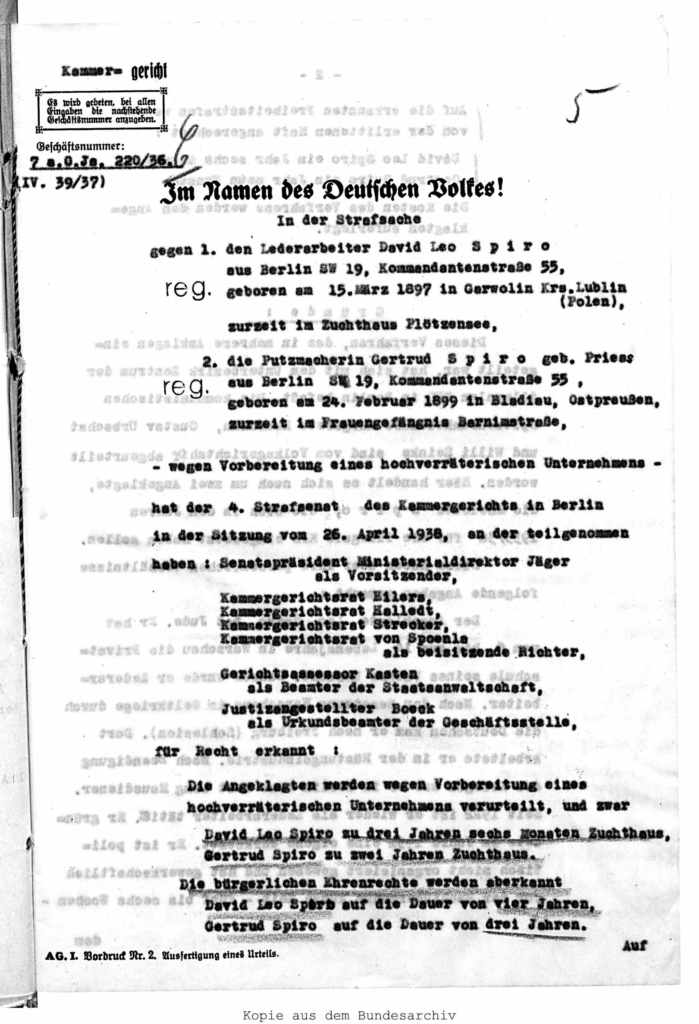

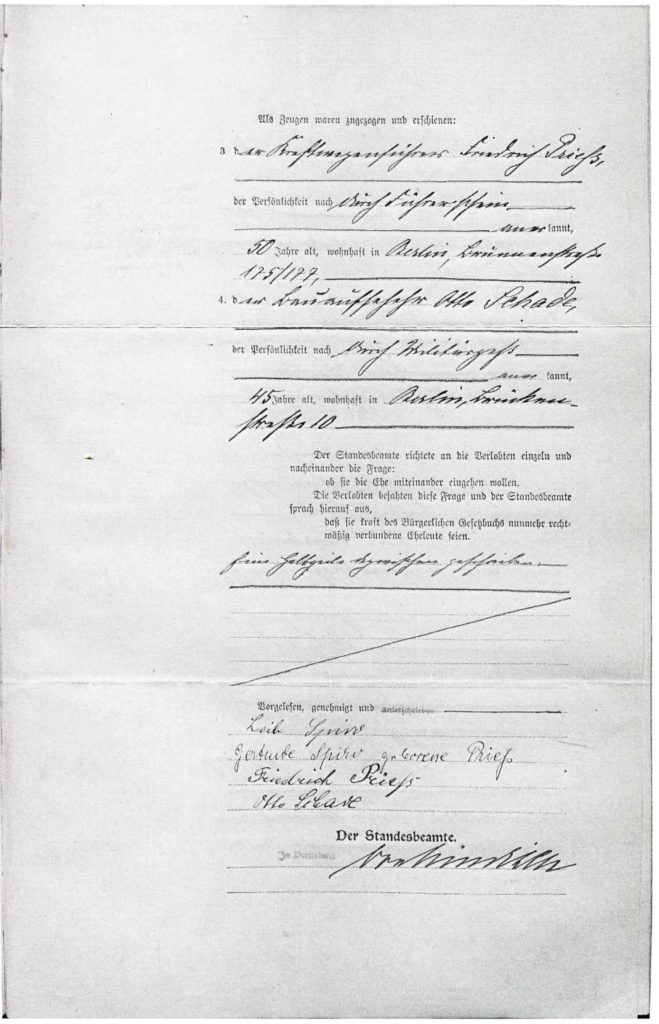

Information about Gertrude’s early life is derived from her marriage record held by the Berlin Landesarchiv and from trial records held by the Berlin Bundesarchiv Lichterfelde. On 3 February 1923, Gertrude married Leo David Spiro, a Jew. Leo was born in Garwolin, Kreis Lublin, Poland, on 15 Mar 1897, the son of Abraham Leiser Spiro and Lea born Graf. He spent his early years in Warsaw, attending the private school run by his father. Leo was a leather worker. The couple had one daughter, Sonia, born in 1925 in Berlin.

Gertrude and Leo in Prison

Gertrude and Leo in Prison

On 22 July 1936, Leo and Gertrude were arrested in Berlin for preparing to commit treason. Their crime was to associate with Margarete Kaufmann and Gustav Urbschat, prominent members of the illegal KDP (Communist Party). They allowed Kaufmann and Urbscat to hold meetings at their apartment, and occasionally allowed them or one of their associates to stay with them for a short period of time. In another incident, Kaufmann asked Gertrude to hide the typewriter she used to create Communist literature.

The couple were in prison for nearly two years before they were brought to trial on 26 April 1938. Leo was sentenced to 3 1/2 years in prison, with partial credit of one year six months time served; Gertrude was given 2 years in prison, with full credit for one year nine months served. Gertrude was presumably released on 26 July 1938, after which she moved (or was expelled) to Warsaw with their daughter Sonia. Unfortunately, Leo was never released. When his sentence was completed on 26 April 1940, he was sent immediately to the Berlin Police Prison, re-arrested, and then sent to the camps.

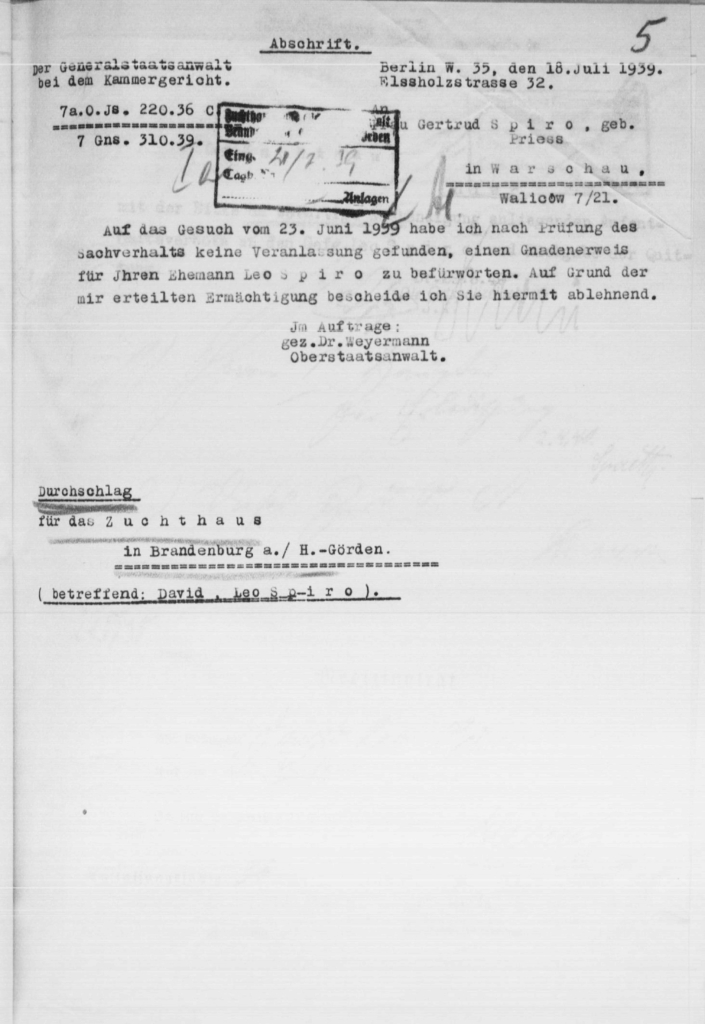

Leo’s prison records obtained from the International Tracing Service have provided us with the earliest records we have of Gertrude in Poland. Buried among the many pages documenting Leo’s movement through the German prison system are two memoranda from July 1939 relating to Gertrude’s request for clemency for her husband. Her return address was given as Walicow 7/21, Warsaw. The correspondence reads:

*****

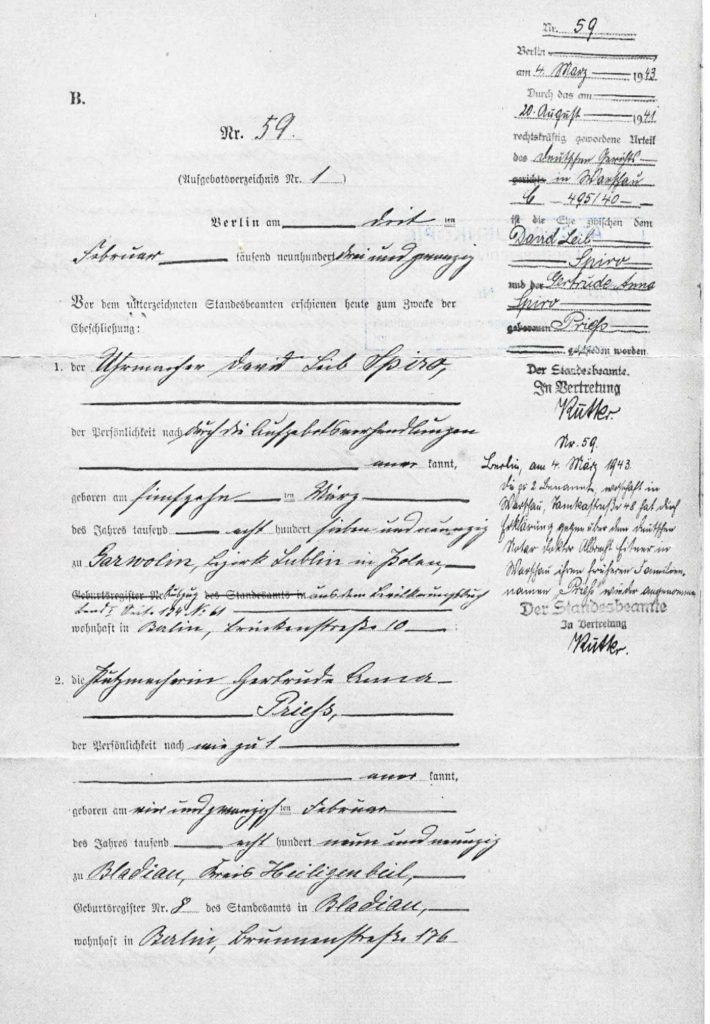

The Board of the Prison and Detention Center

The Board of the Prison and Detention Center

Brandenburg (Havel) – Görden

Subject: Clemency for the Penitentiary Prisoner Leo Spiro

Reference: Request of 27 Jun 1939

To the Attorney General of the Appeals Court

3 July 1939

The Jewish penitentiary prisoner Leo Spiro is serving a prison sentence of 3 years 6 months, less 1 year 6 months time served, for preparing to commit a treasonable act under the above referenced case number. His release date is set at 04/26/1940. In the accompanying petition his wife, who was also convicted of preparing to commit treason to 2 years in prison in the same criminal case, requests a pardon for Leo Spiro, who is to be expelled from the Reich at the completion of his sentence.

Spiro has, in obedience to his responsibilities during his present imprisonment, behaved in an orderly manner and performed satisfactorily. Through his offense, he has abused the hospitality granted to him by the German Empire, by supporting the illegal KDP in 1935-1936 with his actions aimed at its violent overthrow. In this respect, any requirement for the granting of a pardon is negated. I therefore reject the request.

Senior Administrative Officer

*****

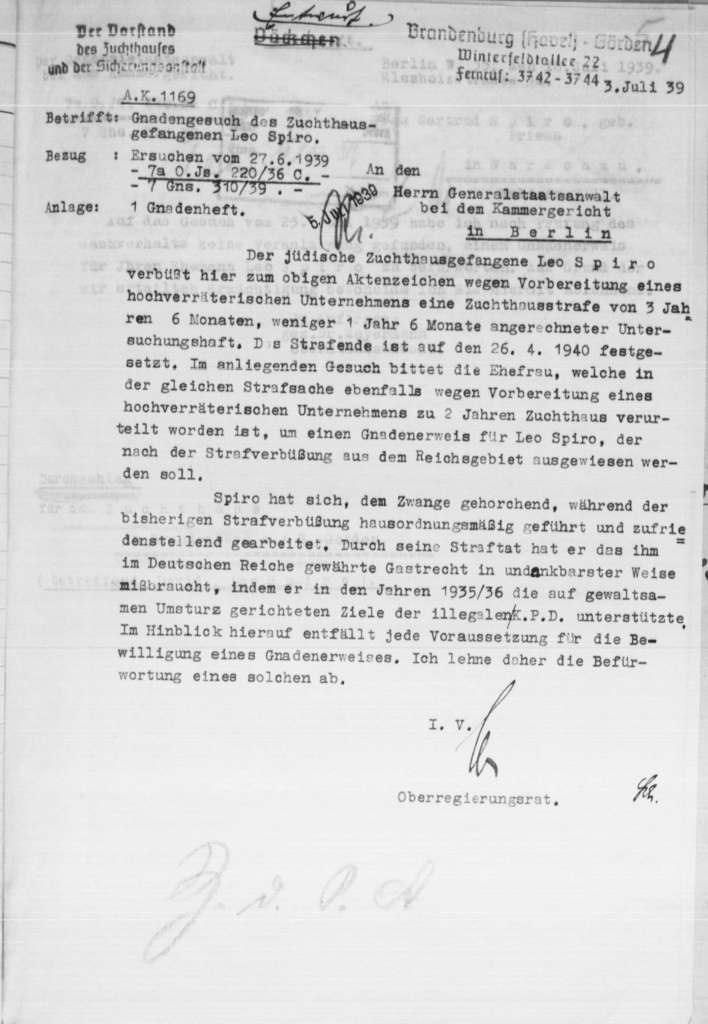

The Attorney General of the Appeals Court

The Attorney General of the Appeals Court

Berlin W 35,

18 Jul 1939

Gertrud Spiro nee Priess

in Warsaw

Walicow 7/21

At the request of 23 Jun 1939, I have, after examination of the facts, found no reason to favor a pardon for your husband Leo Spiro. On the basis of my authority, I deny your request.

On behalf of

Dr. Weyermann

Attorney General

*****

The denial of Gertrude’s request for clemency for her husband sealed Leo’s fate. He never left the prison system. From the Berlin Police Prison in Berlin, he was transported to the Sachenhausen and Ravensbrück concentration camps, then to his death in the Bernburg Euthanasia Center on 25 March 1942. He is buried in a mass grave in Berlin.

Gertrude in Warsaw

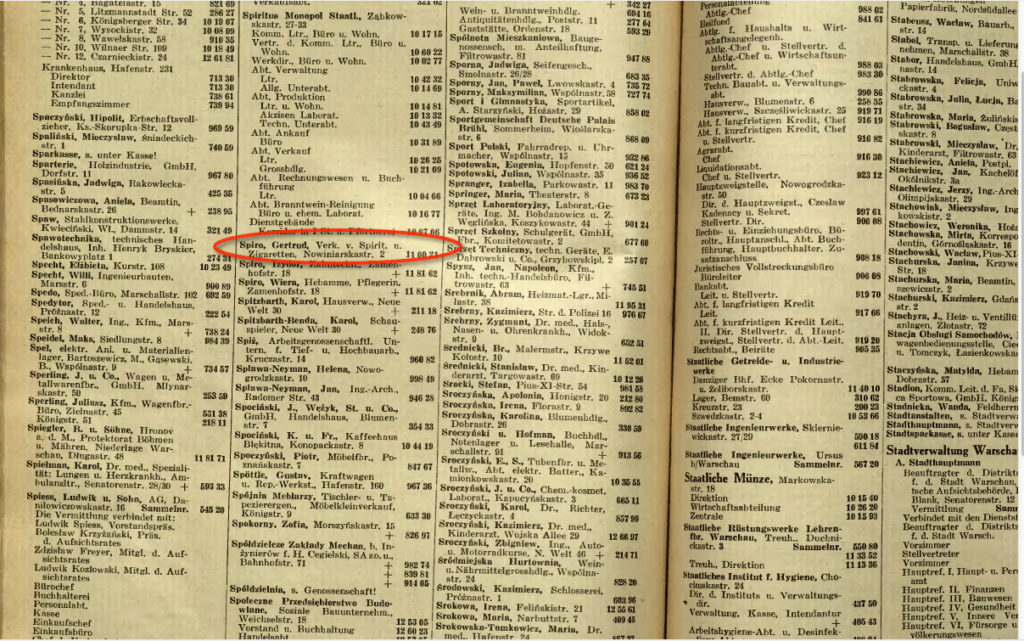

Gertrude seems to have done well in Warsaw. The 1941 and 1942 Generalgouvernment and Warsaw telephone directories show her as the owner of a cigarette and liquor store at 2 Nowiniarksa St, about a half block from the Ghetto wall. This is an interesting location. According to the Ringelblum Archives as quoted by Barbara Engelking in her book The Warsaw Ghetto, A Guide to the Perished City:

“The policeman Jakob Frydman set up a business smuggling goods to the ghetto. The Zglinowicz cafe in Leszno Street was the place where contacts were made. In the cafe, Misza Waserman sat by the telephone and took calls from the Aryan side to say that the goods were ready. Misza replied with a password, indicating the time and guard post one could enter (Wroblewska 1996, 205)”. A similar role was played by a certain cafe on Nowiniarska St. “All the smugglers knew the telephone number 11-33-00 of that cafe, where they could come to terms among themselves and make deals with the players (AZIH, Ring I, 435)”.

The 1939-1940 Warsaw telephone directory reveals that the phone number associated with the cafe belonged to Chaim Szok, 8 Nowiniarska St. It was located in the same building as Gertrude’s shop.

Another interesting aspect of Gertrude’s activities is that cigarettes and liquor are two of the highest priced luxuries during wartime. According to Dr. Engelking’s book, in March 1942, a few months before the major transports from the Ghetto to Treblinka, a pack of cigarettes cost about 0.4 zlotys. In September 1942, as the situation in the Ghetto worsened, one cigarette cost 3 zlotys. By May 1943 during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, a single cigarette cost 250 zlotys. The price of liquor also skyrocketed.

Ghetto Map, Green Inclusions, Blue Exclusions 1941, Nowiniarska St. and Gertrude’s shop are indicated in red

We still don’t know how Gertrude came to own the shop on Nowiniarska St. The Polish State Archives in Warsaw does not have property records for that address. The area was originally a Jewish neighborhood that was included in the Ghetto in early 1941. Later that same year, when the neighborhood was excluded from the Ghetto and became part of the Aryan section, shops appeared along the even number (north) side of Nowiniarska St. Gertrude must have had the right connections to open a shop in such a prime location, especially one next door to a smuggling den.

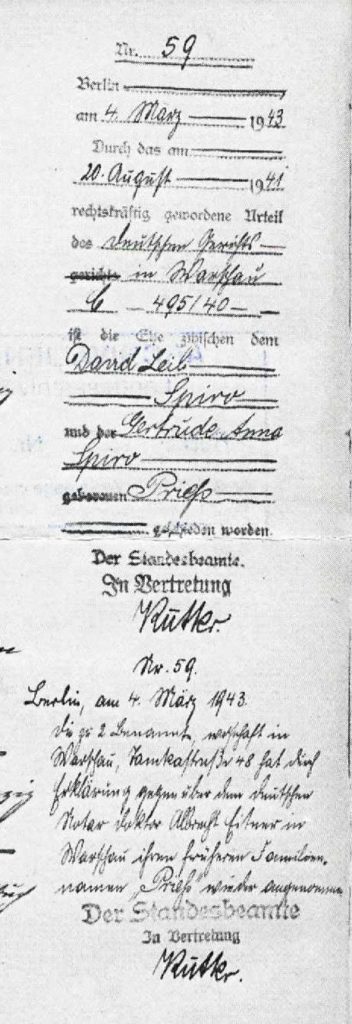

One last detail about Gertrude is provided by a stamp in the upper right corner of her marriage certificate:

Nr. 59

Nr. 59

Berlin, 4th March 1943. Through the court order issued by the German court in Warsaw on 20 August 1941, C 495/40, was the marriage between David Leib Spiro and Gertrude Anna Spiro nee Priess dissolved.

On behalf of the registry office: Rütter

Nr. 59

Berlin, 4 March 1943

The undersigned, resident of Warsaw, Tamkastrasse 48, declared to the German notary Doctor Albrecht Cintner, in Warsaw, that she has adopted her former surname Priess.

Judging by the case number C 495/40, Gertrude must have filed her divorce papers in mid- to late 1940. This would have been somewhat after the date that Leo was to be released from Brandenburg Prison on 26 April 1940. It could be that when her husband was sent to the Berlin Police Prison instead of being released, that Gertrude realized that she would never see him again and decided to divorce Leo. It could also have been a mutual decision, perhaps over concern for the safety of their daughter Sonia. In 1940, Sonia was 15 years old. As half-Jewish, she was officially immune from deportation from Berlin – but the laws in Warsaw were different.

PAWIAK PRISON

Pawiak Prison was originally built in 1835 in Warsaw, to be used by the Polish judicial to incarcerate criminals, but after the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1949, it was converted into a German Gestapo prison. Approximately 100,000 men and 200,000 women passed through the prison, mostly members of the Armia Krajowa (Home Army), political prisoners, and civilians taken as hostages in street round-ups. An estimated 37,000 were executed and 60,000 sent to German death and concentration camps. There were few known escape attempts.

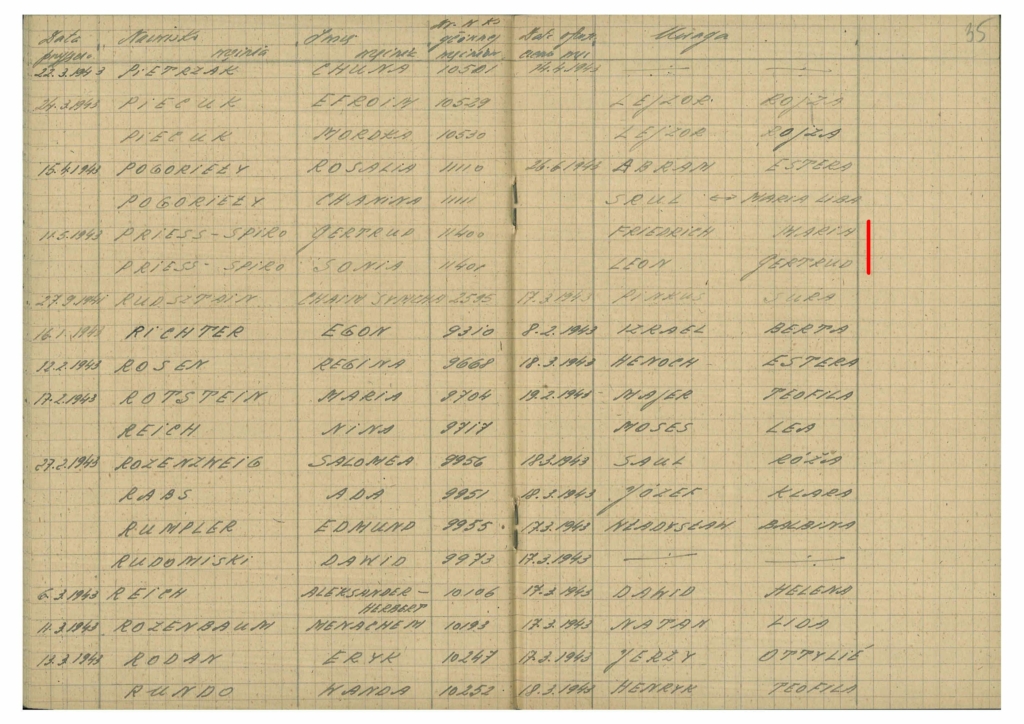

Gertrude and Sonia’s were arrested and imprisoned in Pawiak on 11 May 1943. Their names appear on a copy of a page of the prison registry sent to us by the Jewish Historical Institute, along with their date of arrest and their parents’ names. There is no release date for them. Regina Domanska’s book Pawiak Wiezienie Gestapo (Pawiak Gestapo Prison) provides information on their fate; the mother and daughter were among 141 women transported from Pawiak to Auschwitz on 24 August 1943. Their names also appear on the website Więżniowie Pawiaka on a list of women transported from the prison to Auschwitz. The group was assigned prisoner numbers 55778-55918.

Thinking that was the end of the story for the Priess-Spiro women, I searched the Auschwitz-Berkenau Museum website to find out specifically which prison numbers Gertrude and Sonia were assigned from the group. I made a spreadsheet cross referencing the names of the women on the transport list with their assigned numbers. To my surprise, Gertrude and Sonia were not included among the arrivals. Assuming that the women lined up more or less in alphabetical order to receive their numbers as they were processed, there aren’t vacant numbers on the list close to “Priess” where Gertrude and Sonia would have appeared.

The comparison of the Pawiak and the Auschwitz lists is actually messier than I reported earlier. I’d like to correct a few accounting mistakes I made in a previous chapter of this story. Domanska’s book has 142 names on the Pawiak transport list, but according to the Auschwitz day book, only 141 female prisoners arrived at Auschwitz. Of these arrivals, only 138 female prisoner names are associated in approximately alphabetical order with prisoner numbers on the Auschwitz list – three numbers are vacant.

It would seem straightforward to cross reference the 142 Pawiak names with the 141 Auschwitz names to determine which women were absentees. Of course, it is not as easy as that! There are some complications. Keep reading…

The process of assigning prisoner numbers at Auschwitz is described in Auschwitz 1940-1945, Central Issues in the History of the Camp, Vol II by Tadeusz Iwasko et al, pp 18-20:

The process of assigning prisoner numbers at Auschwitz is described in Auschwitz 1940-1945, Central Issues in the History of the Camp, Vol II by Tadeusz Iwasko et al, pp 18-20:

Transports were received by the Auschwitz concentration camp in exchange for a receipt given to the convoy commandant (Transportführer)…When there was a discrepancy between the number of prisoners in the transport documentation (Transportliste) and the actual number of arrivals, the Auschwitz camp acknowledged the receipt of only of the number of prisoners who actually arrived, regardless of whether they were dead or alive…

One of the first acts required of new arrivals was that they line up in alphabetical order according to their surnames. Then a prisoner from the registration detail (Aufnahmekommando) drew up a handwritten list with consecutive camp serial numbers written next to the names. Each prisoner then received a small card bearing the serial number he or she had been assigned.

*****

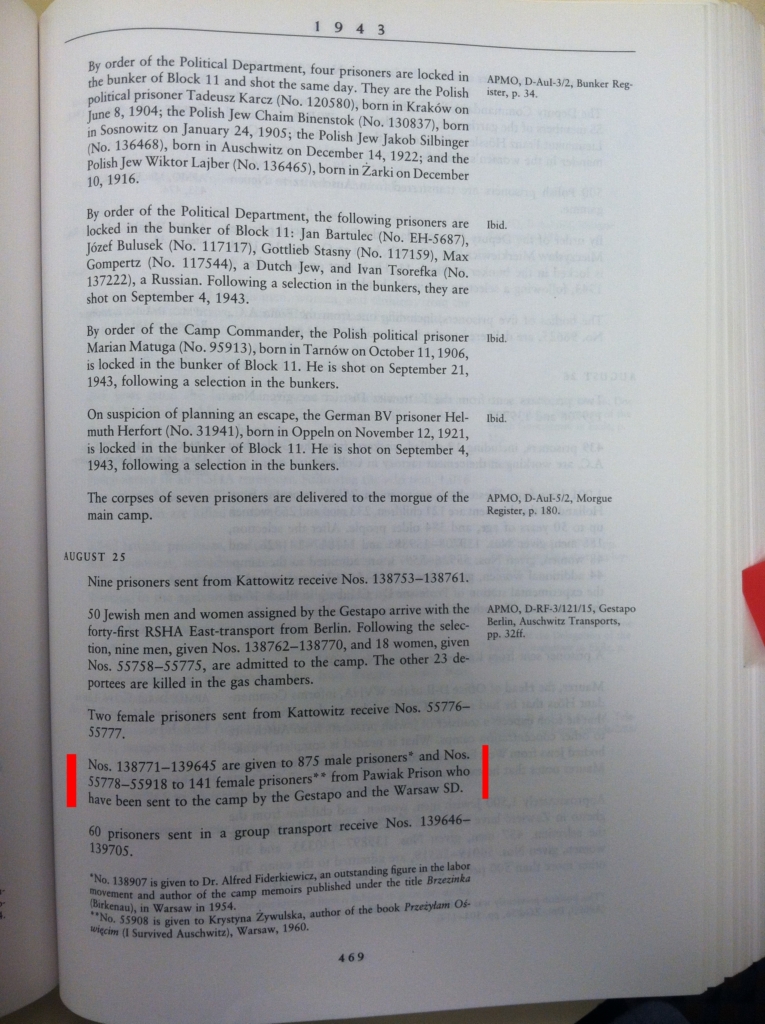

Auschwitz Chronicles 1939-1945, by Danuta Czech, p. 469, offers further insight specifically into Gertrude’s transport as it includes excerpts from the Auschwitz day book:

August 25, 1943

August 25, 1943

Nine prisoners sent from Kattowitz [sic] receive Nos. 13873-138761.

50 Jewish men and women assigned by the Gestapo arrive with the forty-first RHSA east-transport from Berlin. Following the selection, nine men, given Nos. 138762-138770, and 18 women, given Nos. 55758-55775, are admitted to the camp. The other 23 deportees are killed in the gas chambers.

Two female prisoners from Kattowitz receive Nos. 55776-55777.

Nos. 138771-139645 are given to 875 male prisoners and Nos. 55778-55918 to 141 female prisoners from Pawiak Prison who have been sent to the camp by the Gestapo and the Warsaw SD.

60 prisoners sent in a group transport receive Nos. 139646-139705.

*****

From what these accounts tell us, there must have been 141 women who arrived at the camp alive. There must have been 141 women present during the registration procedure because there were 141 numbers assigned to the group that were consecutive with the groups before and after them.

The question is: were Gertrude and Sonia among the 141 women? My opinion is – at least one of them, and possible both of them were absent.

Here is my logic:

- Regina Domanska’s book has 142 women’s names on her list of women transported to Auschwitz on 24 August 1943. It is possible that Pawiak miscounted the number of prisoners on the transport. Alive or dead, there were only 141 arrivals.

- The 141 women who arrived at Auschwitz survived long enough to be registered with the camp. There are 141 numbers available on the list. Numbers were not assigned to dead prisoners.

- Comparing the names on Domanska’s Pawiak list to the Auschwitz prisoner database reveals surprising inconsistencies:

– There are five women on the Pawiak list whose names are not on the Auschwitz list, reducing the number of Pawiak women known to make it to Auschwitz from 142 to 137. They are:

Priess-Spiro, Gertrude

Priess-Spiro, Sonia

Rudnik, Właclawa

Ryngwelska, Irena aka Fijałkowska, Irena

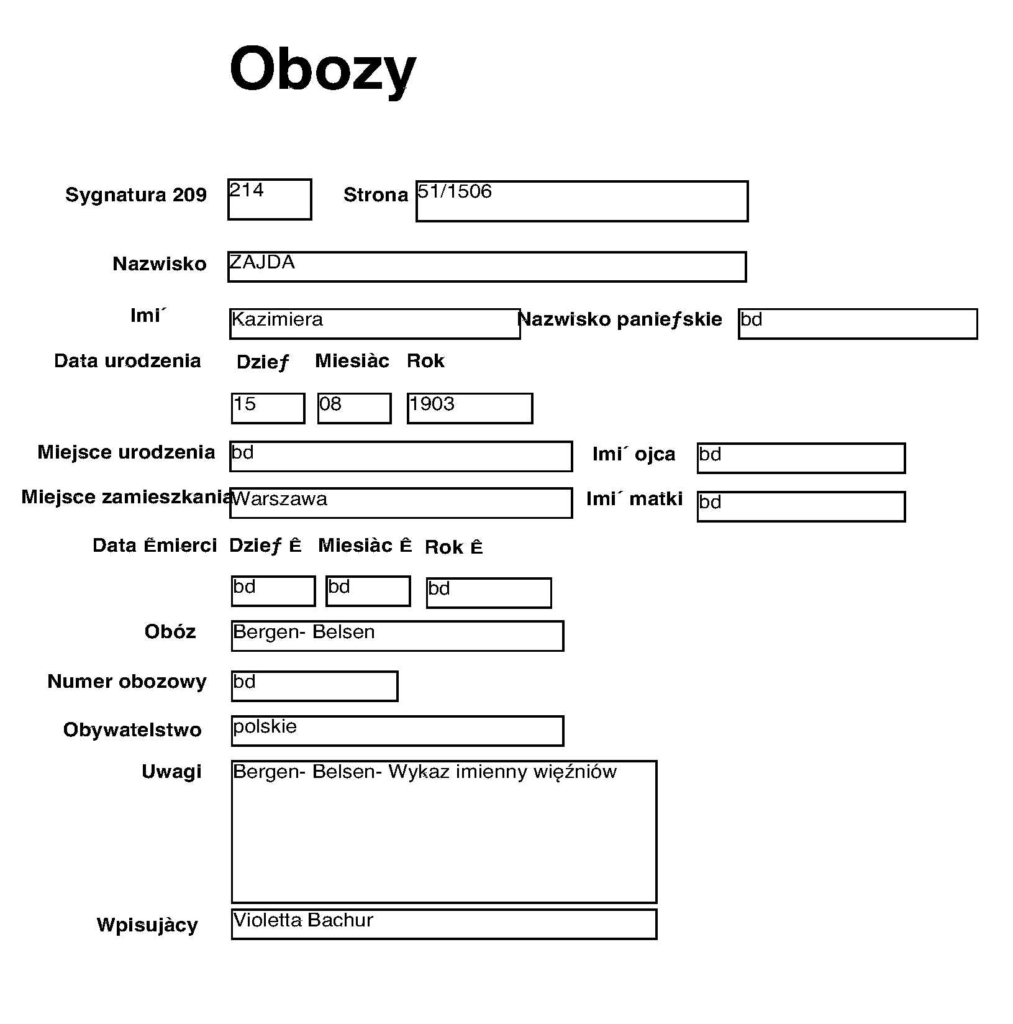

Zadja, Kazimiera

– There is one woman on the Auschwitz list – Stanisława Fijałkowska (No. 55801) who does not appear on the Pawiak list, increasing the number of women known to have been registered at Auschwitz from 137 to 138,

– According to the Auschwitz Museum website, there are three unoccupied numbers on the Auschwitz registration list: 55873, 55885, 55905.

Which of the five women were associated with the three vacant registration numbers? Which two disappeared from the transport?

Correspondence with the Pawiak Museum. the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, and the JHI provides some answers:

from: Muzeum Podleglosci

to: Colleen Fitzpatrick

date: Wed, Nov 26, 2014 at 1:50 AM

subject: RE: Pawiak prisoners

From our information Irena Rogala had nr 55873 and Wacława Rudnik had nr 55875. Unfortunately we don’t have any further information, I suggest you to contact Auschwitz Archive.

Best regards,

The Museum of Pawiak Prison

*****

from: Muzeum Podleglosci

to: Colleen Fitzpatrick

date: Wed, Nov 26, 2014 at 2:07 AM

According to information in our files Wacława Rudnik survived the war. When the Museum was founded in 1960s there were an appeal to contact archive and help to reconstruct the files, many prisoners of Pawiak that survived gave their testimonies, some of these testimonies were written some only oral. Wacława Rudnik left only short oral information about her imprisonment (it is all I wrote you in previous e-mail). Unfortunately we don’t know if she is still alive. Because of Protection of personal data we are not authorized to give you her address. Best regards

The Museum of Pawiak Prison

*****

from: Monika Taras

to: Colleen Fitzpatrick

date: Tue, Dec 2, 2014 at 6:45 AM

Dear Miss Fitzpatrick,

The archives send you the scans of copy list from Bergen-Belsen with the name ZAJDA Kaziemiera born 15.08.1903. She lived in Warszawa. We do not know the date of that copy. Yours sincerely,

Monika Taras

*****

According to the data from the Pawiak Museum and the JHI in Warsaw, we can account for Wlaclawa Rudnik and Kazimiera Zajda. Wlaclawa’s absence from the Auschwitz list was a result of a clerical error. Wlaclawa was assigned No. 55875, bumping Irena Rogala to No. 55873. This rearrangement is consistent with the alphabetical order of the names on the list and matches one of the missing women with one of the vacant numbers.

Kazimiera’s name was probably absent for similar reasons. Her last name Zadja fits in alphabetically at vacant No. 55905. Bergen-Belsen was a common next destination for prisoners at Auschwitz.

| 55903 | Wyczlińska, Anna ? |

| 55904 | Wyrembowska, Irena |

| 55905 | Zajda, Kazimiera |

| 55906 | Zielińska, Jadwiga |

| 55918 | Zielińska, Zofia |

*****

Only one number remains vacant, No. 55885 with only just three candidates that can fill it: Gertrude Priess-Spiro, Sonia Priess-Spiro, and Irena Ryngwelska (Irena Fijałkowska).

The vacant number falls on the list, not in a position consistent with “Priess” but in a position consistent with “Spiro”.

| 55883 | Sokal, Stefania |

| 55884 | Sobieraj, Józefa ? |

| 55885 | — |

| 55886 | Stamirowska, Anna |

| 55887 | Suchanek, Teofila ? |

Another twist was introduced by Paweł Bezak, Archivist at the Pawiak Prison Museum:

from: Paweł Bezak

to: Colleen Fitzpatrick

date: Sun, Dec 4, 2016 at 11:51 PM

Hi Colleen,

We don’t have any information about Stanisława Fijałkowska – only a card of Irena Fijałkowska (sending to: Irena Rynglewska). We know only that she was in a transport from Pawiak to KL Auschwitz, on August 24th, 1943.

No, we don’t think they could be the same person. As you can see in R. Domańska’s book , some names are written in brackets – means that somebody was arrested under false name or used that in a camp.

Nor do we. Sorry.

There is an info, that 141 of arrested women arrived to the camp – but there could be some more send to KL Auschwitz, so, at least one of them could probably die… Maybe we should consider another possibility: some prisoners could even use the names of these, who were killed or died during transport – because they believed that had a bigger chance to survive under false names, due to their nationality or causes that they were arrested.

Regards,

Paweł

*****

There are several possibilities:

(1) The vacant number was assigned to any one of the three women and the other two were not on the transport;

(2) Irena Fijałkowska (aka Irena Ryngwelska) was the same person as Stanislawa Fijałkowska, one of the Priess-Spiro women occupied No. 55885, the other Priess-Spiro was not on the transport,

(3) One of the Priess-Spiro women took the name Stanislawa Fijałkowska, the other took the number 55885, and Irena Fijałkowska-Ryngwelska was not on the transport.

So far, we have not found other records for either of the Fijałkowska women, and the remaining empty spot on the list is consistent with the name Spiro (but not Priess-Spiro).

The status of Gertrude and her daughter Sonia could not be more ambiguous. In two out of three of the possible scenarios, either Gertrude or Sonia or both were not on the transport. We have never considered that Gertrude and Sonia could have been separated, or that one of them died.

I’ve already inquired about the Fijałkowska’s with the Pawiak Prison Museum, the JHI, and with the Auschwitz Museum. Nothing has come of this so far.

THE GERMAN SOLDIER

Of the most obscure characters in this story is the German soldier who acted as the liaison with Pnina’s parents. He was said to be the sweetheart of Sonia Spiro; some versions of the story state he lived at the same address as the Spiros – 48 Tamka St. So far, we have not been able to confirm either of these facts, even though I have spoken to members of the Strauch and Ordega families whose relatives lived there at the time.

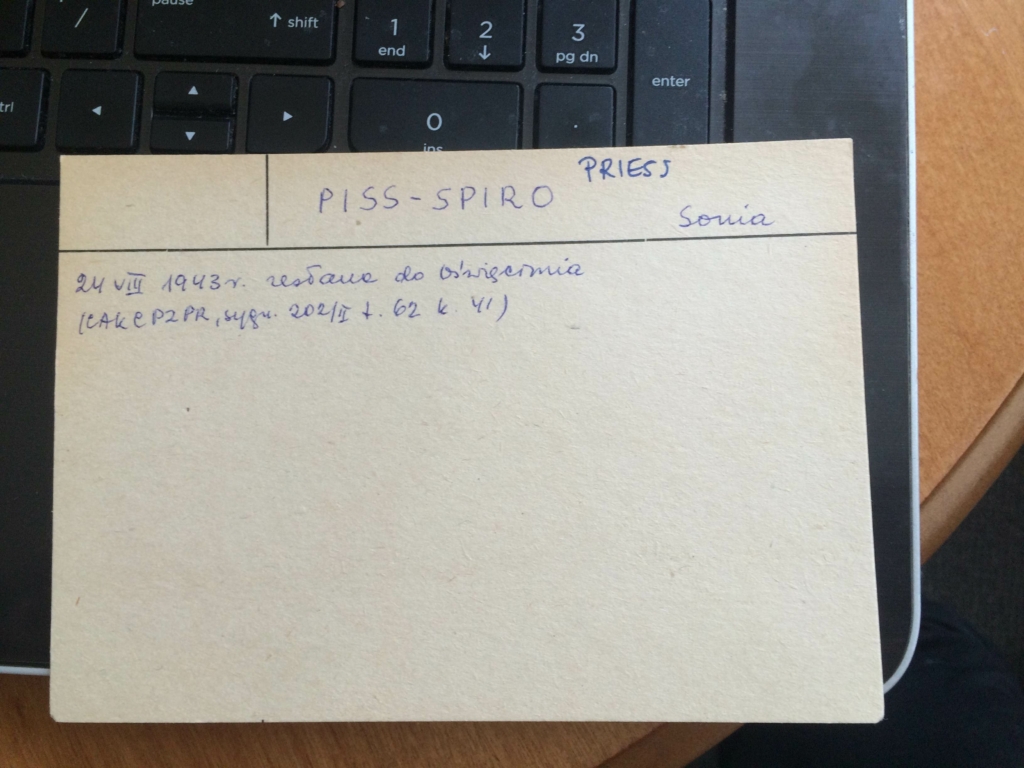

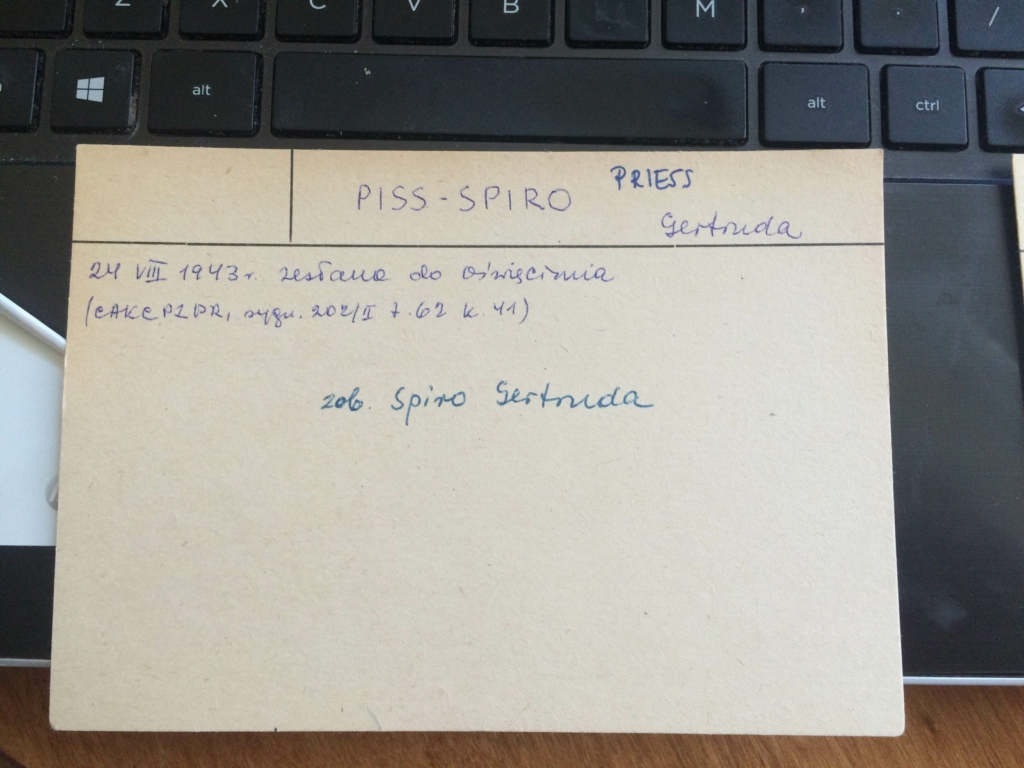

On my recent trip to Pawiak Prison Museum, I discovered an interesting clue to the soldier’s identity. The Museum has a alphabetical catalog of index cards for thousands of the prisoners who passed through Pawiak. These include cards for both Gertrude and Sonia Priess-Spiro. The hyphenated version of their name was probably used because, after her divorce, Gertrude had returned to using her maiden name Priess, while Sonia’s continued to use the last name of her father Leo Spiro. Doubling their last name would have made it easier for them to stay together.

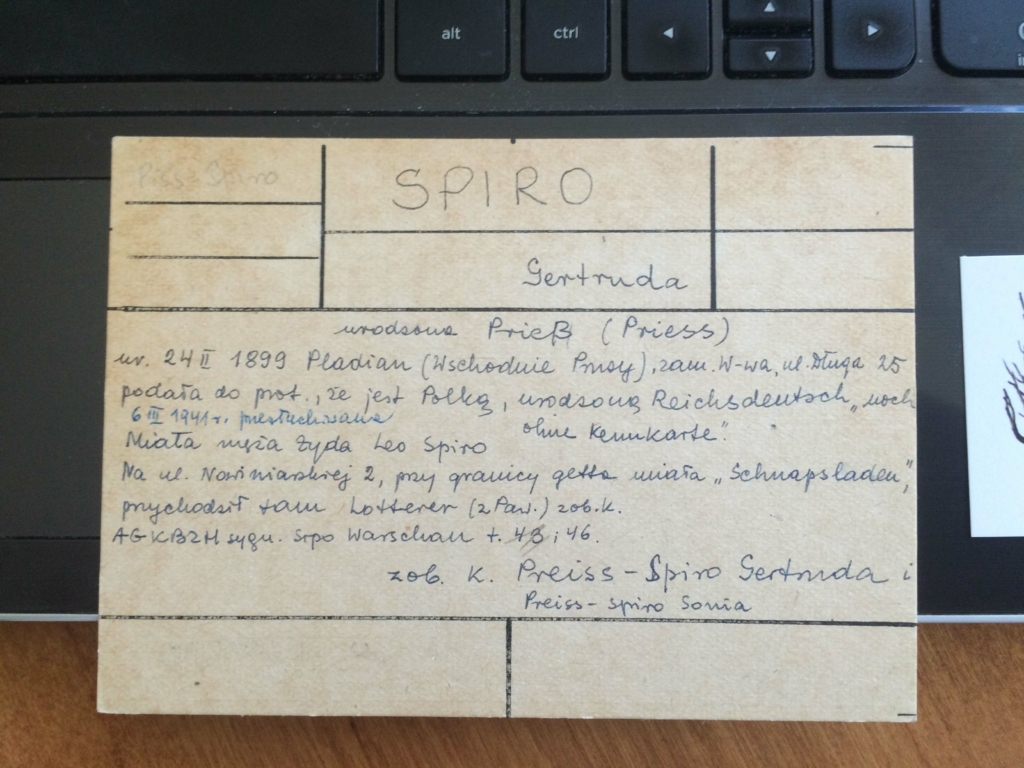

Gertrude has two cards on file. We were already aware of the information on the first card, thanks to the website Więżniowie Pawiaka (Pawiak Prisoners).

Piss-Spiro, Gertruda/Sonia (notated with Priess to upper right)24 August 1943 – sent to Auschwitz.(CACKCP1PR, signature 202/II t. 62 k. 41)

A second card for Gertrude provided some startling information. It read:

Gertruda Spiro

born Prieß (Priess)

Born 24 Feb 1899 Pladiau (East Prussia), lived in Warsaw at 25 Długa St. When she arrived at the prison, she said that she was Polish, but she also said that she was born as a native German (Reichsdeutsch) although without documents.

On 6th March 1941 she was interrogated. She had a husband, a Jew called Leo Spiro. She had a liquor store on 2 Nowiniarksa St. by the border of the ghetto, and Lotterer (from Pawiak) was coming there. (Also see the card for Lotterer).

AGKB2H signature SIPO Warschau t. 48. i. 46

See the card for Priess-Spiro Gertruda and Priess-Spiro, Sonia

*****

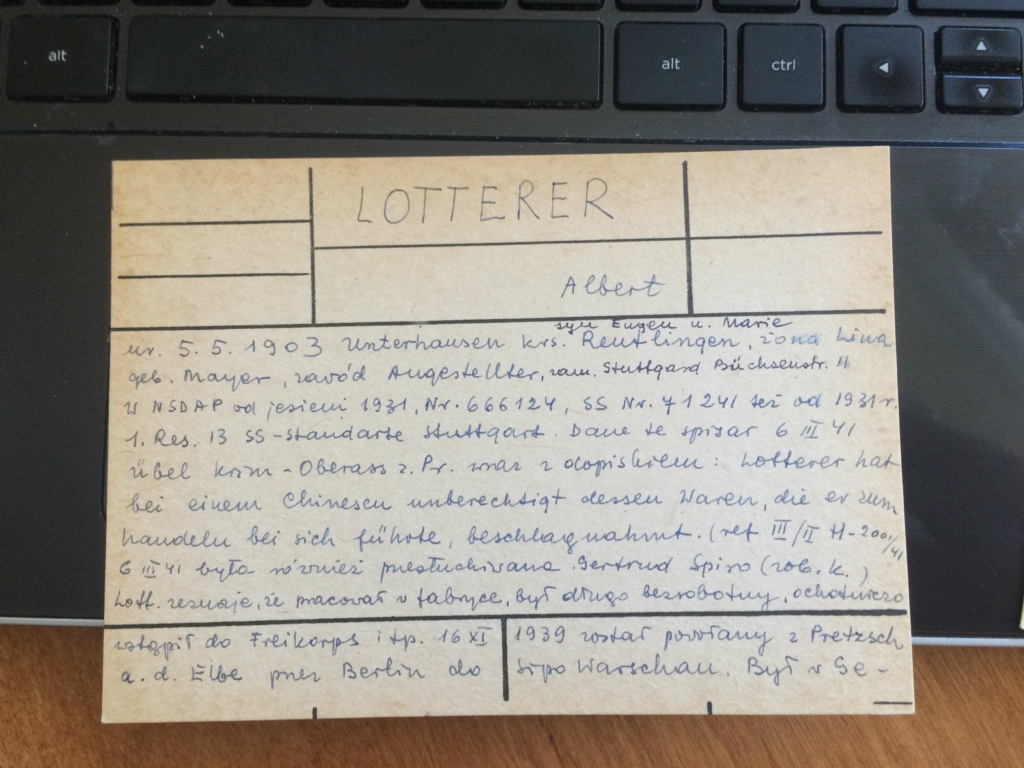

Could Albert Lotterer be the German soldier we have been searching for? Albert Lotterer has a prisoner card, too:

It reads:

Lotterer, Albert

Lotterer, Albert

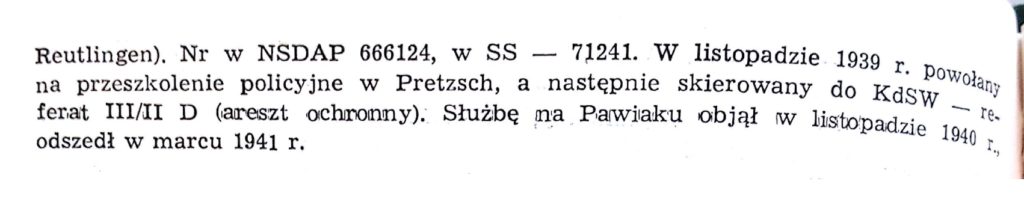

Born 5 May 1903 Unterhausen, Kries Reutilingen, son of Eugen and Marie, wife Lina nee Mayer, occupation – employee, living in Stuttgart, Bucherstr. 11, in NSDAD [National Socialist German Workers Party – Nazi Party], from the fall of 1931 Nr. 666124, SS Nr. 71241, also from 1931.

1st Co. Reserve 13 SS Standard Stuttgart

This information was from an interrogation on 6 March 1941 from the [Übel Kriminal Oberass. z. Pr.] Criminal Court (by?) Police Sergeant of the Secret Police. Lotterer illegally commandeered goods from a man named Chinescu who was prompted to sell them(?). (Ref III/II tl-2001/41). On 6 March 1941, Gertrude Spiro was also interrogated. (See also her card).

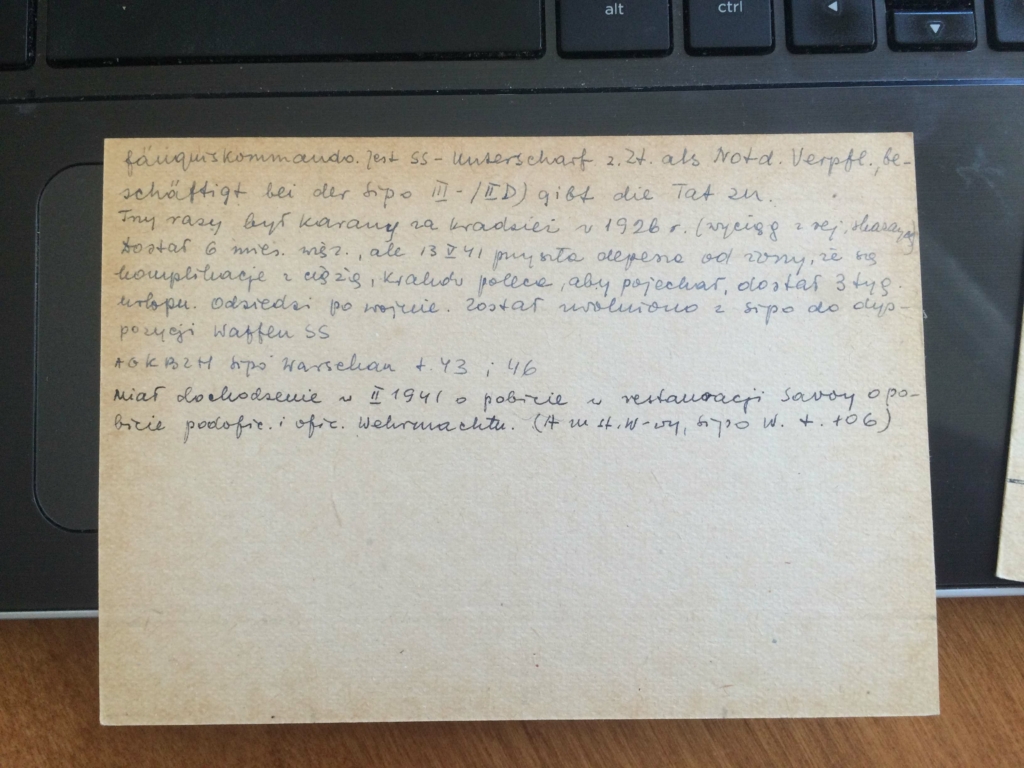

Lotterer said that he was working in a factory for a long time. He had no job. So he volunteered for the FreiKorps, etc. On 16 Nov 1939, he was taken from Pretzsch on the Elba by Berlin to the Security Police Warsaw. He was in the Prison Guards. He is SS Unterscharf (corporal or Jr Sergeant) at present as a Notd. Verpfl. (?), employed by the SIPO III/II D

He was punished three times for theft in 1926 (register of people who were punished), and he got six month in prison. On 13 May 1941, he got a telegram from his wife that there was a problem with her pregnancy. He got an order from Cracow for him to come, so he got three weeks’ vacation. He should get back to the prison after the war. He was also sent by SIPO to the position in the Waffen SS.

AGKB2H SIPO Warsaw t. 43 i. 46

He was interrogated in Feb 1941 for fighting in the Savoy restaurant with an NCO (non-commissioned officer) and an officer of the Wehrmacht. (AMHW – N(?)Y, SIPOW t. 106)

*****

Albert Lotterer’s card provides the first link we have found between Gertrude and a Pawiak prison guard. It’s significant that he was a customer at her liquor store. Lotterer was probably not the only prison guard who frequented the store, but given the fact that Gertrude was interrogated for a crime committed by him, it is reasonable to assume that she knew him better than others. Could her connection to Lotterer or another prison-guard/customer of her store explain how Gertrude and Sonia escaped from the Pawiak transport to Auschwitz?

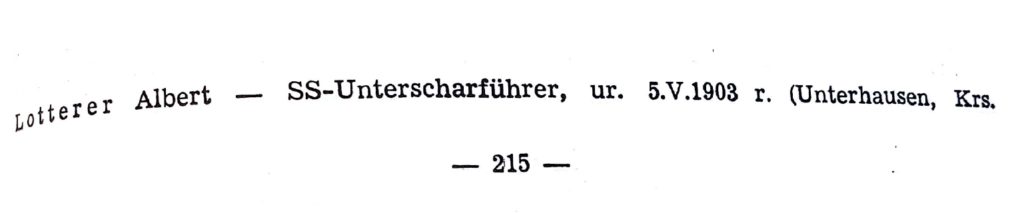

Through inter-library loan, Cate was able to obtain a copy of the Bulletin of the Main Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes Poland, that mentions Lotterer on pp 215-216:

Lotterer Albert – SS-Unterscharfuhrer, born 5 May 1903 (Unterhausen, Kreir Reutlingen). Communist Party No. 666124, SS No. 71241. In November 1939 appointed to train police in Pretsch. and then directed to ACOR – paper III / II D (protective custody). Began service at Pawiak in November 1940, left in March 1941.

This is a bit more than what we knew before – the entry mentions that Lotterer left the Prison in 1941. And we know that he was arrested in March 1941, and that in May 1941 he went to be with his wife during the birth of their child. It’s possible he came back to Warsaw after that and got into the baby-smuggling business. Who knows?

We are searching for Lotterer descendants, hoping they will have more information about their father or grandfather Albert. Lotterer’s card provides a lot of personal information that could be helpful for this, for example, his birthdate, his parents’ names, his wife’s name, and the fact that he had a child born in 1941.

That son or daughter might still be alive. We’ve been looking.

Note that the SIPO file for Lotterer (AGKB2H SIPO Warsaw t. 43 i. 46) is the same as that for Gertrude, (AGKB2H SIPO Warsaw t. 48 i. 46) with the same file number (46) but a different page number (48 versus 43). Franek, our team member from Poland, recently ordered a copy of this file from the Institute of National Remembrance in Warsaw.

Besides this, I’ve discovered Lotterer’s military records at the German Bundesarchiv. I expect to receive copies of his file before Christmas. I’m now waiting for a response from the Deutsche Dienstelle, the repository of historical information on German soldiers. It would be unbelievable if somewhere in Lotterer’s military or criminal records it’s mentioned that he was arrested for smuggling, especially for smuggling babies.

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part I – Pnina, Otwoc, and the Kaczmareks

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part II – Pnina, Wolfgang, and the Warsaw Ghetto

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part III – Gertrude and Sonia Spyra

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part IV – Wolfgang and Adele’s Eyewitness Account

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part V – Gertrude and Sonia’s Escape

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part VI – Our Search for Gertrude Spiro

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part VII – Gertrude’s Other Children?

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part VIII – Gertrud and Leo’s Trial

Who Am I? What is My Name? – Part IX – Gertrude’s Sisters!

Who Am I? What is My Name? – Part X – Gertrude’s Marriage and Divorce

Who Am I? What is My Name? – Part XI – Berlin, Warsaw, and the German Soldier