I recently traveled to Berlin and Warsaw to personally research in the various German and Polish archives. My hope was to find more information about Gertrude Priess-Spiro and her circle of acquaintance and friends, towards the goal of finding the birth identity of Pnina Gutman, whom she helped smuggle from the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942. I feel that if we can identify the people and organizations that Gertrude was involved with during the War, we may be able to find clues that lead us to Pnina’s family.

Although my initial search of the German and Polish archives was not successful, I later discovered information that may lead to the identity of the German soldier, the most obscure character in Pnina’s story, but perhaps the most important. The German soldier was responsible for putting Pnina’s parents in touch with Gertrude Spiro who eventually arranged to have her smuggled from the Ghetto. Identifying the German soldier would put us one step away from Pnina’s parents.

Many of the repositories I visited did not yield new information. Although I spent several days at the Berlin Bundearchiv Lichterfeld (German National Archives in Lichterfeld), I was only able to find a few more scraps of information about Gertrude and Leo’s trial and arrest. I already knew the basic story from the documents that the Archives had already sent me: The Spiros were arrested in July 1936 for allowing Communist Party members to use their apartment to hold meetings, and because Gertrude agreed to hide a typewriter used by Communist Party operative Margarete Kaufmann to produce subversive literature.

The couple was in prison for nearly two years before they were brought to trial in April 1938. Leo was sentenced to 3 1/2 years in prison, with partial credit of one year six months time served; Gertrude was given 2 years in prison, with full credit for one year nine months served. Gertrude was released in July 1938, after which she moved to Warsaw with their daughter Sonia. Unfortunately, Leo was never released. When his sentence was completed on 26 April 1940, he was sent immediately to the Berlin Police Prison, then to Sachenhausen, and then to Ravensbruck concentration camps. He died in the Bernberg Euthanasia Camp on 25 March 1942.

One new piece of information I discovered at the Bundesarchiv, however, was that although Alfred Roehrs and his wife Martha Maria Priess (Gertrude’s sister) were also arrested in connection with Gertrude’s and Leo’s activities, they successfully convinced the court that they were innocent of any wrongdoing, and were released.

My second stop in Berlin was at the Berlin Landesarchiv (Berlin City Archives). Prior to my visit, I requested a search of the Einwohnermeldekartei (EMK), residency cards issued to all German citizens. They found none for the extended Priess-Spiro family, including Gertrude’s parents Friedrich and Mari Priess, Gertrude, Leo, their daughter Sonia, Alfred and Berta Gerlach, and Ernst and Maria Gerlach, Gertrude’s two brothers-in-law and their wives, her sisters. It was explained to me by the Head Archivist Martin Luchtenhandt, that many of the records had been destroyed during the war.

The Landesarchiv Berlin holds 2.8M Einwohnermeldekartei for Berlin residents from 1875-1948. The collection is incomplete due to heavy damage during the war.

I also asked the Landesarchiv about birth records from East Prussia, where Gertrude and her two sisters were born. I had been told that they were archived in the Landesarchiv, but even knowing from Gertrude’s marriage record that her birth had been recorded in Register No. 8 in Bladiau in 1899, was no use – 95% of the records from that area (now known as Kaliningrad) had been destroyed.

My last request at the Landesarchivs was related to the birth, marriage, and death records that they have not posted online. I was hoping to find the death records of Frederich and Maria Priess, as an indication of when the family may have left their residence on Brunnenstrasse.

Unfortunately, the Landesarchiv could not offer much help. Beyond the 1942 online death records for Berlin Mitte, the district where the Priess family lived, there were only a few years that have been digitized; otherwise the original hard copy registers have to be searched by hand. The digitized files include:

1943 Deaths

1944 Deaths

1945 Deaths K-R & S-Z

1946 Deaths

Although I found a death record for an Alfred Roehrs who was not Gertrude’s brother-in-law, along with a few Gerlachs, I could not find the death record for any member of the extended Priess-Spiro family.

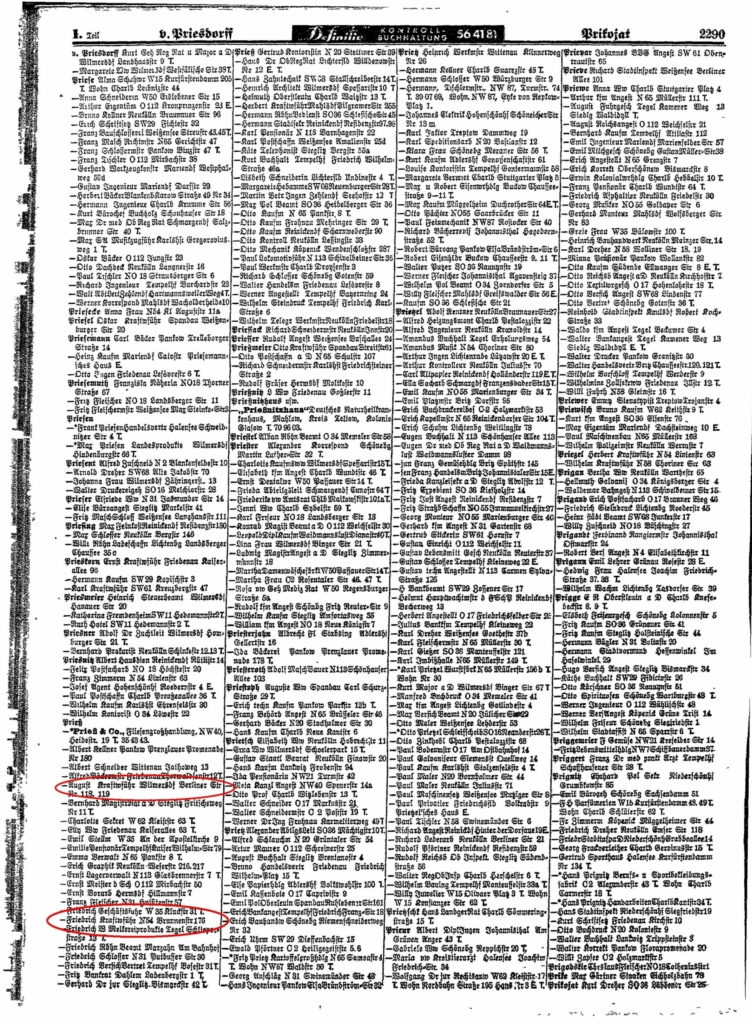

The last repository I visited in Berlin was the Zentral- und Landesbibliotek (ZLB) that holds the Berlin telephone and city directories. I had already tracked the Priess and Spiro families through 1943 using the directories that are available on the ZLB website. The few hard copy or microfiched directories that the ZLB has available (for both East Berlin and West Berlin) dating after the war did not have any Priess, Spiros, Gerlachs, or Roehrs family members listed.

My experience in Warsaw was also initially frustrating. I started at the Jewish Historical Institute, but I was told they only assisted beginning genealogists with their research, and discouraged personal access to reference materials. The JHI houses the Ringelblum Archives, a detailed chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto created by Emanuel Ringelblum. While this would have provided an interesting background to events in the Ghetto, it is written in Polish, and has not yet been translated into English.

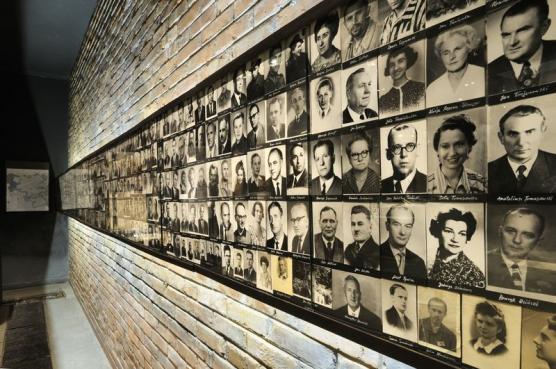

My last research stop at the Pawiak Prison Museum finally brought me the success I had hoped for. The museum’s curator Paweł Bezak gave me a thoughtful tour of the prison, commenting that it was rare for an American to visit the museum for research purposes. We walked down the main hall, where several reconstructed cells were on view. As Paweł explained, although the cells were small, they typically held perhaps a dozen prisoners, with little room to stand or sit. The only source of air was a small window high up on the far wall.

There was a display on children born while their mothers were prisoners, along with artwork and beautiful items of clothing that the prisoners secretly produced from scraps of cloth or string. He guided me through exhibits on prison hygiene and the prison hospital, explaining that prisoners were often brought there to recover after torture or severe beatings, only to be returned to the prison for a second interrogation. The hospital was nevertheless a haven where prisoners (and guards) felt safe and received excellent medical care. The doctors were often resistance workers who passed personal messages and information to and from the outside. In one of the rooms, there was a rogues gallery of Pawiak prisoners, notable political figures, members of the resistance, artists, musicians, writers, and others captives who are perhaps not so well known. I promised Paweł I would send him whatever I had about Gertrude so that her picture and her bio could be added to the exhibit.

As Paweł explained, not much of the original structure remained; it was mostly destroyed in 1944 by the Nazis, along with about half of the prison’s documentation. Only part of the front gate and a cell door or two survived intact along with the memorial tree in front of the prison. The women’s section, known as Serbia, was completely destroyed; it was once located across what is now the main boulevard Aleja Jana Pawla II.

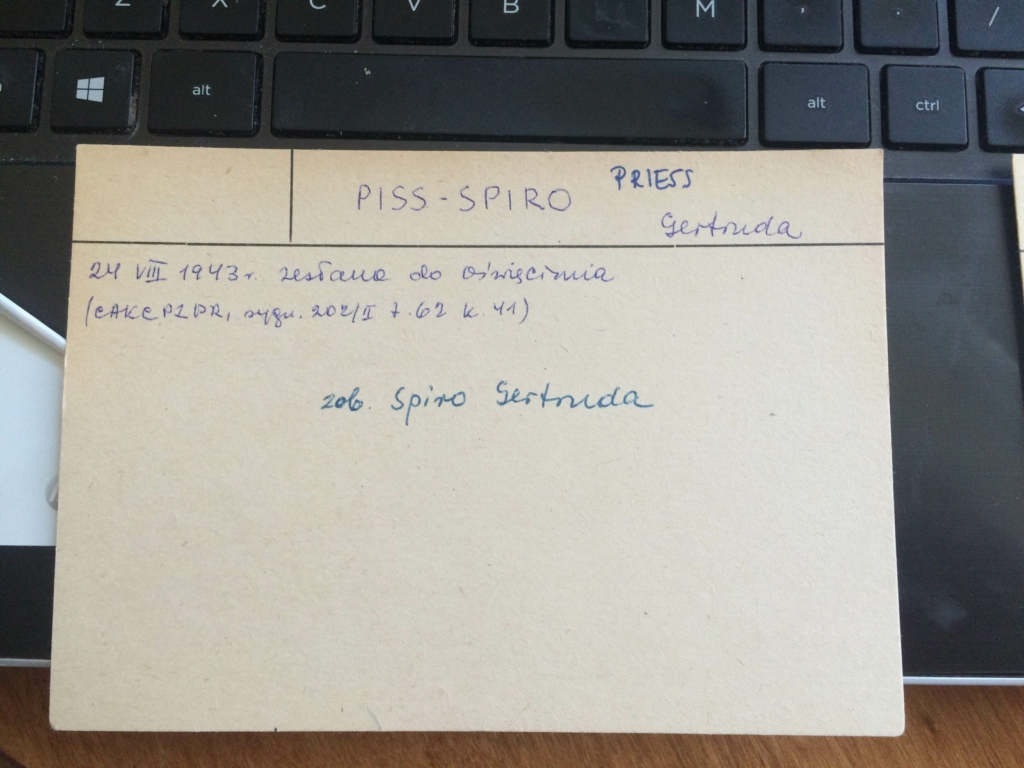

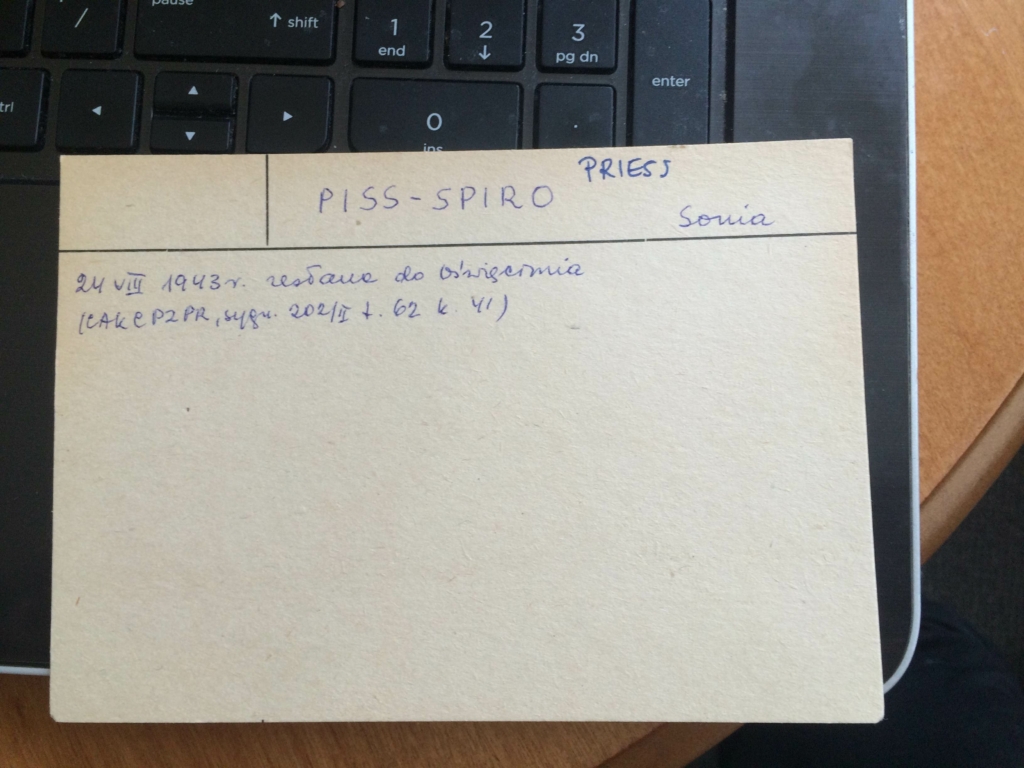

At the end of the tour, Paweł and I went to the museum office to look through the large alphabetical card file of Pawiak prisoners. He pulled cards on Gertrude Piss-Spiro and Sonia Piss-Spiro. I was already aware of the information on these cards from the list of Pawiak prisoners discovered online by Cate Bloomquist a while back.

Piss-Spiro, Gertruda/Sonia (notated with Priess to upper right)

24 August 1943 – sent to Auschwitz.

(CACKCP1PR, signature 202/II t. 62 k. 41)

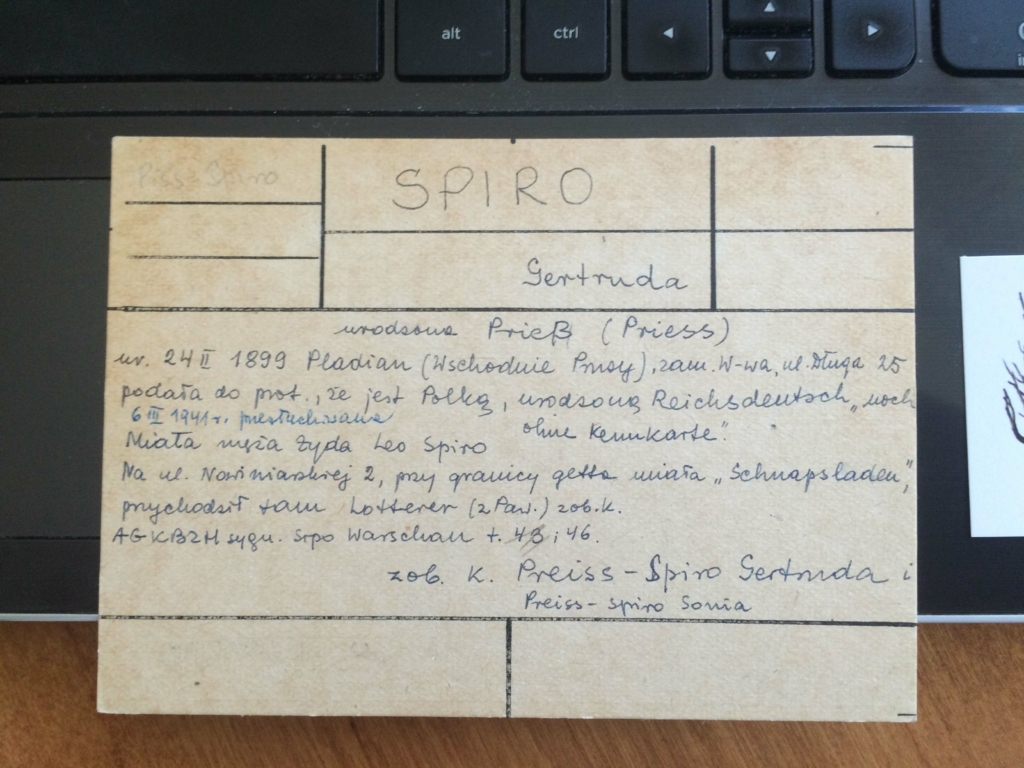

Surprisingly, Paweł discovered a second card for Gertrude. It read:

Gertruda Spiro born Prieß (Priess)

born Prieß (Priess)

Born 24 Feb 1899 Pladiau (East Prussia), lived in Warsaw at 25 Długa St. When she arrived at the prison, she said that she was Polish, but she also said that she was born as a native German (Reichsdeutsch) although without documents.

On 6th March 1941 she was interrogated. She had a husband, a Jew called Leo Spiro. She had a liquor store on 2 Nowiniarksa St. by the border of the ghetto, and Lotterer (from Pawiak) was coming there. (Also see the card for Lotterer).

AGKB2H signature SIPO Warschau t. 48. i. 46

See the card for Priess-Spiro Gertruda and Priess-Spiro, Sonia

*****

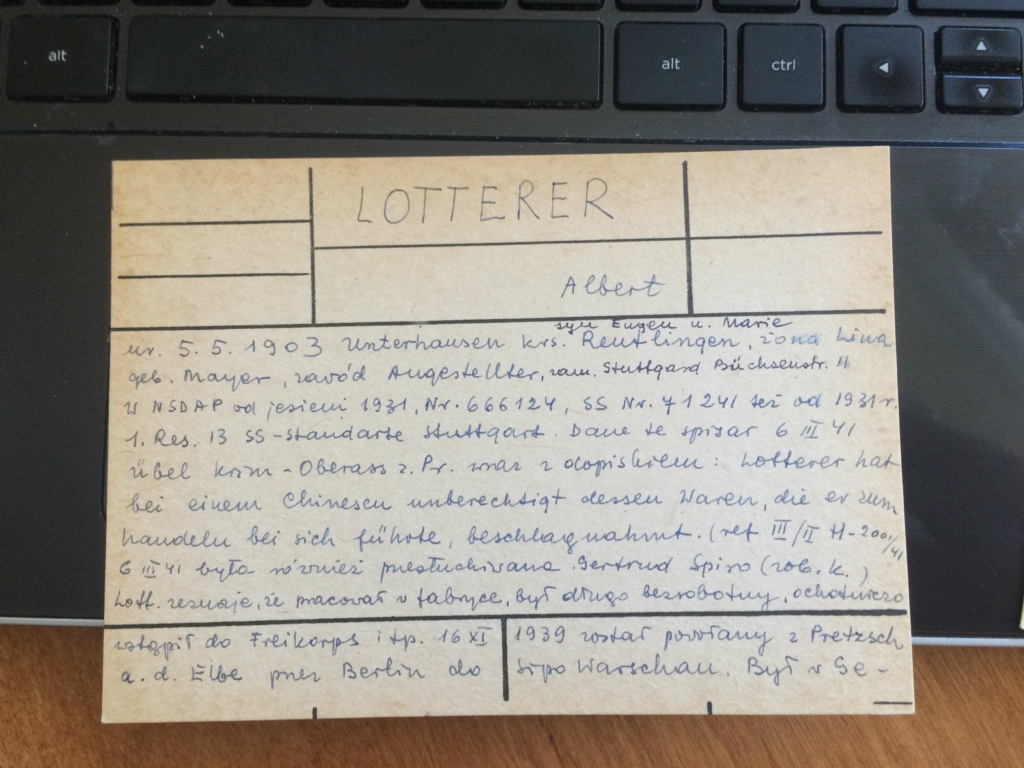

I gasped. Could Albert Lotterer be the German soldier we have been searching for? I asked Paweł to find Lotterer’s card.

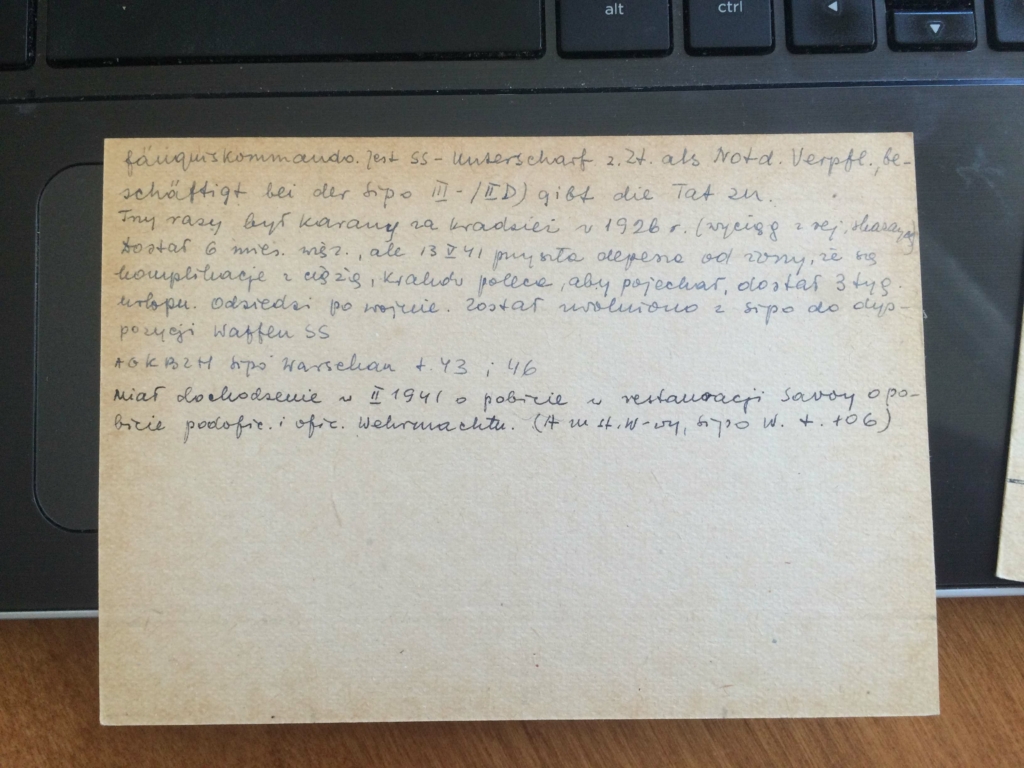

It read:

Lotterer, Albert

Born 5 May 1903 Unterhausen, Kries Reutilingen, son of Eugen and Marie, wife Lina nee Mayer, occupation – employee, living in Stuttgart, Bucherstr. 11, in NSDAD [National Socialist German Workers Party – Nazi Party], from the fall of 1931 Nr. 666124, SS Nr. 71241, also from 1931.

1st Co. Reserve 13 SS Standard Stuttgart

This information was from an interrogation on 6 March 1941 from the [Übel Kriminal Oberass. z. Pr.] Criminal Court (by?) Police Sergeant of the Secret Police. Lotterer illegally commandeered goods from a man named Chinescu who was prompted to sell them(?). (Ref III/II tl-2001/41). On 6 March 1941, Gertrude Spiro was also interrogated. (See also her card).

Lotterer said that he was working in a factory for a long time. He had no job. So he volunteered for the FreiKorps, etc. On 16 Nov 1939, he was taken from Pretzsch on the Elba by Berlin to the Security Police Warsaw. He was in the Prison Guards. He is SS Unterscharf (corporal or Jr Sergeant) at present as a Notd. Verpfl. (?), employed by the SIPO III/II D

He was punished three times for theft in 1926 (register of people who were punished), and he got six month in prison. On 13 May 1941, he got a telegram from his wife that there was a problem with her pregnancy. He got an order from Cracow for him to come, so he got three weeks’ vacation. He should get back to the prison after the war. He was also sent by SIPO to the position in the Waffen SS.

AGKB2H SIPO Warsaw t. 43 i. 46

He was interrogated in Feb 1941 for fighting in the Savoy restaurant with an NCO (non-commissioned officer) and an officer of the Wehrmacht. (AMHW – N(?)Y, SIPOW t. 106)

*****

This translation may not be exact. For example, we could not decipher whether Albert Lotterer stole property from someone named Chinescu or from someone from China. Either way, Albert Lotterer’s card provides an important link between Gertrude and a Pawiak prison guard. It is unlikely that Lotterer was the only prison guard who was a customer of her liquor store, but given the fact that Gertrude was interrogated for a crime committed by him, it is reasonable to assume that she knew him better than some of the others. Could her connection to Lotterer explain how Gertrude and Sonia escaped from the transport to Auschwitz?

Lotterer’s card provides a lot of information that could be used to find him in the German records – his birthdate, his parents’ names, his wife’s name, and the fact that he had a child born in 1941. That son or daughter might still be alive.

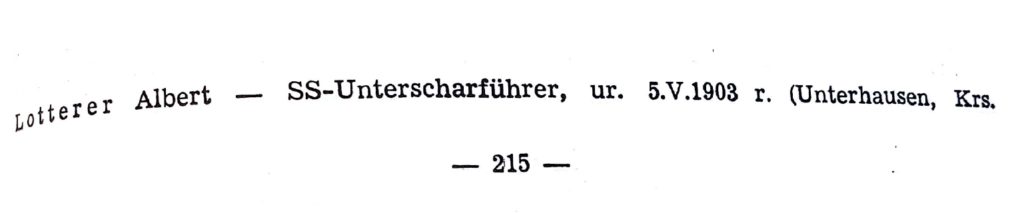

So far, we have not discovered very much about Albert Lotterer, but we are on the job. Through inter-library loan, Cate was able to obtain a copy of the Bulletin of the Main Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes Poland, that mentions Lotterer on pp 215-216.

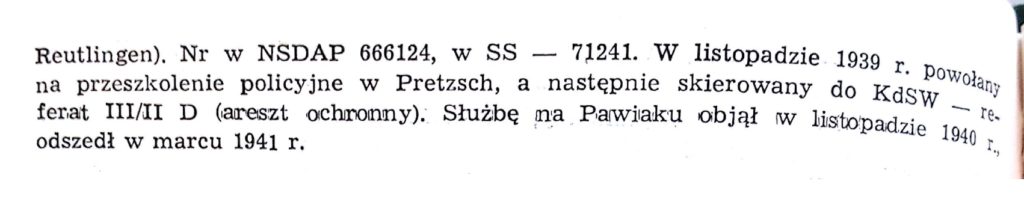

Lotterer Albert – SS-Unterscharfuhrer, born5 May 1903 (Unterhausen, Kreir Reutlingen). Communist Party No. 666124, SS No. 71241. In November 1939 appointed to train police in Pretsch. and then directed to ACOR – paper III / II D (protective custody). Began service at Pawiak in November 1940, left in March 1941.

Lotterer Albert – SS-Unterscharfuhrer, born5 May 1903 (Unterhausen, Kreir Reutlingen). Communist Party No. 666124, SS No. 71241. In November 1939 appointed to train police in Pretsch. and then directed to ACOR – paper III / II D (protective custody). Began service at Pawiak in November 1940, left in March 1941.

This is a bit more than what we knew before – the entry mentions that Lotterer left the Prison in 1941. And we know that he was arrested in march 1941, and that in May 1941 he went to be with his wife during the birth of their child. It’s possible he came back to Warsaw after that and got into the baby-smuggling business.

Who knows?

We are now searching for Lotterer descendants, hoping they will have more information about their father or grandfather Albert. I’ve already written to the Deutsche Dienstelle, the repository of historical information on German soldiers. I also have a friend who is traveling to the US National Archives in Washington next week who has promised to search for information on Lotterer that might be in the Archives’ German military collections. I’ve checked Facebook and the German phone book for Lotterers, and will follow up with what I discover in the near future.

More later…

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part I – Pnina, Otwoc, and the Kaczmareks

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part II – Pnina, Wolfgang, and the Warsaw Ghetto

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part III – Gertrude and Sonia Spyra

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part IV – Wolfgang and Adele’s Eyewitness Account

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part V – Gertrude and Sonia’s Escape

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part VI – Our Search for Gertrude Spiro

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part VII – Gertrude’s Other Children?

Who Am I? What is My Name? Part VIII – Gertrud and Leo’s Trial

Who Am I? What is My Name? – Part IX – Gertrude’s Sisters!

Who Am I? What is My Name? – Part X – Gertrude’s Marriage and Divorce

Who Am I? What is My Name? – Part XI – Berlin, Warsaw, and the German Soldier