After eight and a half decades, there was little left of the child’s body. Only a small piece of wrist bone and the crowns of three tiny baby teeth had survived the inclement weather and damp, slightly acidic soil.

In the spring of 2002, when Parr and Ruffman determined that the child was not Gosta Paulson based on a mismatch between the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) obtained from the bone shard and DNA provided by a maternally-linked Paulson relative, the teeth became more significant in the identification efforts. Dr. E. J. Molto, an anthropologist and the director of the Paleo-DNA Laboratory at Lakehead University, suggested that the three teeth belonged to “quite a young child”. The teeth were sent to Dr. Christy Turner at Arizona State University in Tempe, who agreed with his assessment.

There were five other male children about two years old or younger who died on the Titanic: Eugene Francis Rice (2 1/2 years), Sidney Leslie Goodwin (19 mos), Eino Viljami Panula (13 mos), Alfred Edward Peacock (7 mos), and Gilber Sigvard Danbom (5 mos). Parr and Ruffman concentrated on finding maternally-linked relatives of the two youngest children for DNA comparison. When in the summer of 2002, these two children were ruled out by mtDNA analysis, it was time to take a much closer look at the teeth.

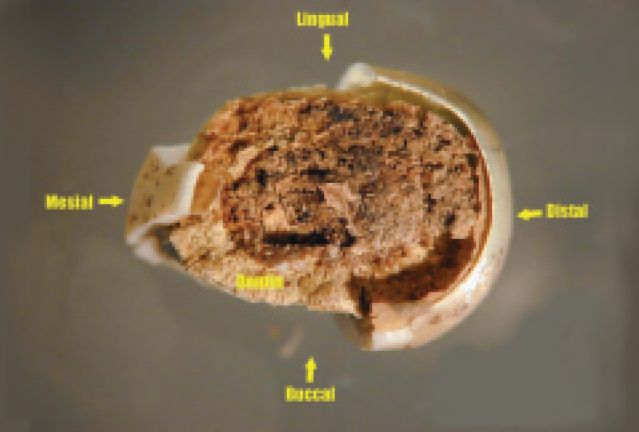

Bruce Pynn, an oral and maxillofacial surgeon in Thunder Bay, suspected that one of the teeth might contain dentin from which additional mtDNA could be extracted. Having a second mtDNA extraction would confirm the DNA profile obtained from the first bone-shard extraction, which had been partially contaminated. Pediatric dentists Keith Titley and Gajanan Kulkarni, and dental anthropologist John Mayhall at the University of Toronto identified the three teeth as the maxillary right second primary molar, the mandibular left primary cuspid, and the mandibular right first primary molar of the child. Furthermore, based on the state of development of the crowns, the lack of root development, and the absence of wear, the teeth were estimated to have come from a child between 9 and 15 months old. Eugene Rice was ruled out not only by an mtDNA mismatch, but also because he was 2 1/2 years old.

Upon examination by a scanning electron microscope, one of the teeth revealed dentin where the enamal layer had flaked off. The dentin was visible around the edges of the interior of the tooth, with debris filling the pulp chamber. The tooth was sent to Dr. Scott Woodward at the ancient DNA laboratory at Brigham Young University in Provo, UT, where a new mtDNA extraction was performed. The mtDNA obtained matched the original mtDNA that had been extracted earlier from the bone shard, confirming that the earlier analysis had been correct.

Two children remained, the 13-month-old Finnish child Eino Panula, and the 19-month-old English child Sidney Leslie Goodwin. The mtDNA of the family references for both children matched that obtained from the remains, indicating that they had a common maternal ancestor within the past 2,000 years. Neither child could be ruled out on the basis of the mtDNA data alone, but taken together with the evidence of the age of the child provided by the teeth, on November 6, 2002, Parr and Ruffman announced that the Unknown Child on the Titanic had been identified as 13-month-old Eino Panula.

Doubts soon arose about whether the identification was correct, however, based on the shoes of the child that had been preserved at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. The shoes were thought to be too large for a 13-month-old child; they would have certainly fallen off before the body was recovered almost a week after the disaster.

Clarence Northover, a Halifax Police Department Sergeant in 1912, helped guard the bodies and belongings of the Titanic victims. According to his grandson Earle Northover, “Clothing was burned to stop souvenir hunters, but he was too emotional when he saw the little pair of brown, leather shoes about fourteen centimeters long, and didn’t have the heart to burn them. When no relatives came to claim the shoes, he placed them in his desk drawer at the police station and there they remained for the next six years, until he retired in 1918.” Clarence Northover moved to Ontario when he retired as Deputy Chief in 1919. In 2002, his grandson Earle Northover decided the shoes belonged back in Halifax and donated them to the Museum, which performed extensive research to authenticate the shoes before accepting them into its collection.

The 1912 Coroner’s report of the child included a description of a pair of “brown shoes”. The identification of the shoes as those of the Unknown Child was supported by research through catalogues and consultation with clothing and footwear museums to show that the style of the shoes are appropriate for the period, roughly 1900 – 1925, and that they were likely manufactured in England. Chemical tests were made to look for traces of seawater and an electron scanning microscope was used to search for saltwater diatoms but the results were inconclusive. The testing found large amounts of salt on the shoes, but the trace elements did not exactly match the proportions in sea water. The testing lab suggested that the chemical components may have been distorted by salts in the tanned leather, by washing or by abrasion.

According to Dan Conlin, the Museum’s Curator,

“We hear from people all the time who think they have objects from Titanic. Unsually nice people who have something in the family or bought something from an antique shop which they think or hope is from Titanic: key tags, steward’s badges, door plates, bells, belt buckles and more deck chairs than I can remember. They inevitably turn out to be wishful thinking.

“However, Northover’s shoes seemed very different from the start. The family’s story had the ring of plausibility connected to a significant person and institution in Halifax of 1912. Earle’s grandfather had retired as Halifax’s deputy polie chief. He told his sons, who told their children how grandfather Clarence had guarded the Halifax morgue where Titanic’s victims were brought after the sinking. When the discarded clothes were swept up, he did not have the heart go burn the tiny pair of baby’s shoes but kept them in a box at his desk in the police station and they went to Ontario with him when he retired.

“Museums have a high standard of authenticity Starting with the Northover’s oral history, we searched newspapers, city directories, police personnel records, coroner’s reports, period footwear catalogues, shoe historians on two continents and the latest in scientific testing. Taken together, the documentary evidence confirmed Northover’s story.”

If the shoes had indeed belonged to the Unknown Child, could the identification of the child as Eino Panula have been in error? While the assessment of the age of the child based on the teeth was the opinion of a group of world odontological experts, it was still subjective. The initial DNA analysis, although objective, had indicated that the child could be either the Panula or Goodwin baby.

The responsibility of identifying the child now returned to the ancient DNA community, with the hope that additional DNA analysis could genetically distinguish between the Panula and Goodwin families. Identification of the tiny baby who died decades ago now depended on some of the most sophisticated technology on earth.

To be continued…

Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV (Conclusion)

8 Responses

Thank you for posting this research! I have been looking for photos of Titanic children lost at sea that night for an art doll project I am working on. I had read about the unknown child, and I love reading about DNA research results. I am reading all 4 parts. Again, Thank You.

You’re welcome! There is a lot on the Titanic. You might want to read more on the Encyclopedia Titanica website. Colleen

Thanks, I’ll check that out!

Hello there, i am a forensic anthropology student myself. And i know back in the 1912, our career was either a joke or at his doorstep. And believe it or not ,the unknown children identification worldwide is a sad nightmare for most of us. Cause such small remains are so fragile that most of their molecular structure gets destroy at the minimum soil instability. I am glad that the little boy’s chapter, has come to a closure. And yes after decades of entropic decay, the pulp cavity, is the only place where you can find any genetic information, if its it to be found at all. Thanks for all. I am glad to know that there are yet people interesting in bringing peace to those who cannot afford it themselves.