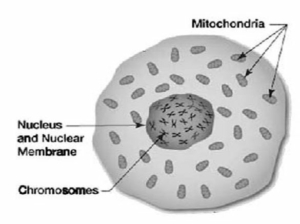

Cell with Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA

To understand what happened next, you have to know a little about mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Mitochondrial DNA is contained in small, football-shaped inclusions outside the nucleus of a cell. It’s widely believed that mitochondria were once independent bacteria that invaded primitive cells millions of years ago. Instead of being digested, these bacteria took up residence in the cell, forming a symbiotic relationship with it. The cell provided them with food and water, and the mitochondria provided the cell with energy for metabolism and heat. The arrangement worked out so well that millennia later, a human cell has up to 1,000 mitochondria, each carrying five to ten copies of its own genome.

A mitochondrion

Mitochondrial DNA is passed along the exclusively female line of the family. A mother passes it to all of her children, but only her daughters pass it on to the next generation. My brothers and my sister and I have my mother’s mtDNA, but only my sister has passed it on to her children. My brothers’ children inherited their mtDNA from their mothers, who are my sisters-in-law.

Not many people understand why this happens. An egg cell is large, containing hundreds of mitochondria. The sperm is small, with only a few in its tail. In the act of fertilization, the sperm injects its genetic material into the egg, but is otherwise destroyed along with its mitochondria. The fertilized egg divides, becoming an embryo that develops into a fetus that eventually is born as a child carrying the mitochondrial DNA of only his or her mother.

Back to the Unknown Child…

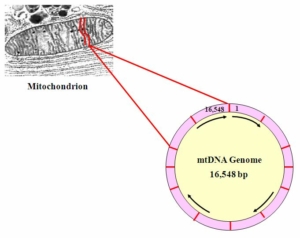

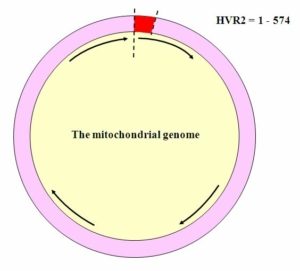

The mitochondrial genome is shaped as a ring, 16, 563 or so bitpairs (bp) long. The positions are numbered starting at the “top” with 1 clockwise to 16,563. Not everyone has exactly 16,543 bit pairs in their mtDNA genome. It is common for the mtDNA genome to experience insertions and deletions, making it slightly longer or slightly shorter than this.

The mitochondrial genome is shaped as a ring, 16, 563 or so bitpairs (bp) long. The positions are numbered starting at the “top” with 1 clockwise to 16,563. Not everyone has exactly 16,543 bit pairs in their mtDNA genome. It is common for the mtDNA genome to experience insertions and deletions, making it slightly longer or slightly shorter than this.

Mitochondrial DNA is abundant compared to Y-DNA, the other type of DNA often used for identifying males. There can be up to 10,000 copies of the small (16,563 bp) mtDNA genome per cell, but there is only one Y-chromosome, about 50 million bp in length. Identification using ancient or degraded DNA usually relies on mtDNA, since the probability of obtaining enough of the right kind of Y-DNA for analysis is usually much lower.

HVR2

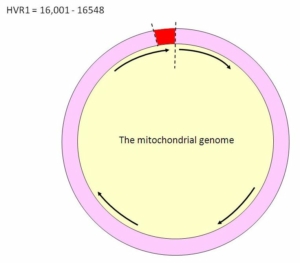

The two sections of mtDNA that are used for identification purposes are known as Hypervariable Regions 1 and 2 (HVR1 and HVR2). These make up the “control region” of mtDNA. They are well-characterized and easy to work with. HVR1 is the segment of mtDNA extending between positions 16001 and 16563. It is usually the segment tested first.

When the original mtDNA tests had been performed on the Unknown Child, only the HVR1 region had been tested. That is, only low resolution tests had been done. This had been sufficient to rule out four of the children. However, because the DNA profile (called the haplotype) of the Unknown Child is very common – the HV haplotype is shared by about 15% of Western Europeans – it is not surprising that the HVR1 results of two out of the six candidates matched those of the Unknown Child. Further DNA testing should have been done before an identification was announced, but because the age estimate given by the teeth was thought to be reliable, it had not been considered necessary.

After doubts arose about the identity of the child, a new round of DNA testing was performed on the HVR2 region, extending between positions 1 and 574. It is usually the second region that is tested to improve the resolution of the analysis. The results of the second round of testing again ruled out the same four children. They also showed that the HVR2 profile of the Goodwin family reference matched that of the remains, but the Panula reference showed one difference, at position 146. While this might seem to exclude Eino Panula, forensic identification guidelines suggest that an exclusion be made on the basis of two differences because of the high mutation rate of mtDNA. Family references are often far removed in the famly tree from the person whose remains may be under examination, so that it is possible that in the intervening generations a random mutation can occur in the family genome. Ruling out the Panula baby based on a single mismatch could result in another mistaken identification, considering how common the haplotype was, and the contamination that had been present in the earlier round of analysis.

So in forensic terms, the second round of testing failed to rule out either child.

There were only two remaining DNA tests possible. One was a last attempt to obtain Y-DNA from the remains, but there was only a remote chance that any Y-DNA had survived, and there had never been any effort made to locate paternal references. The focus had been on finding mtDNA references for the candidate children. The second hope was to test the coding region of mtDNA, the region outside the HVR1 and HVR2 control region. However, the first two attempts to distinguish the children using standard testing of the coding region failed. We were quickly running out of options.

To be concluded…

Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV (Conclusion)