The discovery of gold at Sutters Mill, CA in 1848 promised untold wealth for those who had the resources and stamina to outlast the competition. At the dawn of the California Gold Rush, there were no laws governing property rights; prospectors depended on a system of staking claims to protect their discoveries. Early prospectors did well, earning many times what they would have taken in as common laborers. But within a short time, the techniques of extracting gold became more efficient and sophisticated – far beyond the financial resources of the individual 49er. The tens of billions of dollars of gold recovered from the hills of California were ultimately controlled by only a few. Many later prospectors returned home empty-handed.

We are now experiencing a new gold rush, not to mine nuggets of metal from the earth, but rather to mine nuggets of information from our DNA. Companies that were early into the market did well. But over the last twenty years or so, as technqiiques of extracting genomic information have become more efficient and sophisticated, the billions and perhaps trillions of dollars worth of information extracted from the human genome have come under the control of only a few. Many companies have not had the resources to outlast the competition.

DNA databases were not a new concept. For years, the medical industry had been mining databases of genetic variants to predict and characterize disease and for use in drug development. The CODIS database had already been formalized for use by law enforcement in 1994, and in 2000 included the profiles of nearly half a million offenders, along with over 20k forensic profiles from unidentified remains. Both types of DNA databases are subject to federal regulation.

But the introduction of DNA-on-a-stick by Oxford Ancestry, Relative Genetics, and Family Tree DNA prompted a new kind of gold rush – a race to control the growing, and largely unregulated DTC DNA testing industry.

In the early days, there seemed to be little concern that genetic genealogy data would be used by DTC companies for other kinds of commercial gain. The Y-STRs used for genetic genealogy tests had originally been selected for forensic use in identifying individuals, without revealing information about someone’s ethno-ancestry or his physical characteristics. Genetic genealogists posted their Y-STR test results on public websites and shared them freely without much concern for personal privacy.

That started to change around 2006 with the founding of 23andMe, the first DTC company to offer autosomal SNP testing. Partially financed by information giant Google, the company’s goal was to mine the genome for data that could be marketed to pharmaceutical companies and medical research groups. Unlike earlier DTC DNA companies, 23andMe’s strength was not simply how much data it controlled, but how much that data was worth to other organizations.

From the beginning, 23andMe leveraged concern over the privacy of personally identifying information to its advantage. While the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) was already in place to protect privacy and the security of health information, 23andMe is not covered by HIPPA because it is not a health care provider. 23andMe created its own terms of service, privacy, and informed consent agreements to protect the consumer’s personal privacy, while allowing the company to exploit the consumer’s anonymized genomic data as it wished.

In other words, 23andMe created two streams of revenue, one through the familiar front door with DTC customers willing to pay for its Personal Genomic Service (PGS), and the other through a new back door from selling their data to the medical establishment and to research groups.

In the early days of the California Gold Rush, there was relatively little conflict or crime. Everyone believed they would become rich. There was competition to grab ownership of the best claims and disputes over water rights, but there was little need to steal from anyone. As miners moved from one camp to the next, they developed a set of informal practices that were more or less universally accepted among the mining communities in the West. These pertained to the maximum size of a claim and how long a claim could be left unworked before it was forfeited to another prospector.

But as more people and companies moved in to take advantage of the wealth, “claim jumping” became common; violence and crime were on the rise. Civil law was in the hands of the people. And even though informal mining practices were supported by state and territorial legislation, open mining on public land was still illegal and unregulated under federal law. Because California had just recently been acquired by the US from Mexico at the end of the Mexican American War, the western mining industry operated in a legal vacuum.

After the Civil War, a kind of federal claim jumping was attempted. Eastern Congressmen regarded western miners as squatters robbing the federal coffers of revenue needed to pay the country’s enormous war debt. They introduced bills into Congress to seize western mining claims from their owners and auction them to the public, or to send armed troops to the mining areas to expel the miners and allow the government itself to work the mines for the benefit of the treasury. Western representatives argued that miners and prospectors were performing valuable services to the nation by promoting commerce and settling new territory.

In 1864, Congress voted in favor of the miners, passing a law (30 U.S.C. §§ 22-42) that instructed courts deciding questions of contested mining rights to ignore federal ownership, and defer to the miners in actual possession of the ground. Legislation over the next few years was consolidated into the General Mining Act of 1872 that legalized mining on public lands, and gave discoverers the right to stake claims to extract valuable deposits from the ground. The Act of 1872 also set the price for land assumed under the mining act as $2.50 to $5.00 per acre.

In a similar way, as the potential of the DTC industry grew well beyond traditional genealogical interests, competition became fierce for shares of the lucrative market, while the spectre of government control appeared on the horizon.

In August 2013, in its push to increase its database to 1M customers, 23andMe expanded its efforts to market its PGS with television ads claiming its tests could assess health risks, with the tag line “Change what you can, manage what you can’t”. In November 2013, the FDA issued a warning ordering the company to “immediately discontinue marketing the PGS until such time as it receives FDA marketing authorization for the device”. The FDA’s concern arose over the lack of analytic clinical validation of those claims, and how the public might use information provided about breast cancer mutations and warfarin-related genotype results, in the absence of consultation with a medical professional.

It is tempting to label the FDA’s warning to 23andMe as a type of claim jumping, an attempt by the government to grab control of the DTC market. But the issues are much more complex. It is the FDA’s job to protect the consumer by requiring that statements made about the safety, effectiveness, and security of health-related medical devices and tests are accurate and that devices and tests do what they are claimed to do. In other words, the FDA’s order to 23adMe to cease marketing its PGS should not necessarily be interpreted as an attempt to divert control of the DTC industry away from 23andMe, but rather as the FDA’s obligation to the consumer to ensure that he gets what he pays for and doesn’t get hurt in the process.

Complying with the FDA’s order, in December 2013 23andMe removed health-related results from its product line, noting on its website that “At this time, we have suspended our health-related genetic tests to comply immediately with the [FDA] directive to discontinue new consumer access during our regulatory review process.” Company sales slowed down considerably, although 23andMe continued to offer ancestry-related information and raw data without interpretation.

However, the 23andMe genomic Gold Rush hardly came to a standstill. The FDA’s warning only prevented 23andMe from returning health-related information to its customers – the company’s back door was still open for business.

Since it was founded, 23andMe had been collaborating with pharmaceutical companies to mine customer genomes for clues to various genetic disorders. In 2014 it announced a collaboration with Pfizer to enroll more than 10,000 patients with colitis or Crohn’s disease in its database to look for genetic clues to the cause of those bowel disorders. This was followed in January 2015, by an upfront payment from Genentech of $10 million, with further milestones of as much as $50 million – one of ten deals the company had signed with large pharmaceutical and biotech companies. Including $115M the company raised through a 2015 Series E offering, the company’s total capital investment reached $241M.’

Raising the stakes even higher, in March 2015, 23andMe announced it was going into the pharmaceutical business. Not content with harvesting and consolidating genetic information from its PGS for sale to the pharmaceutical industry, the company planned to capture a greater economic share of the value of its genetic databases. A drug in clinical trials could be worth hundreds of millions of dollars; placing that drug on the market could be worth billions.

Think “Gold Rush on Turbo”.

These developments seem to dwarf the February 2015 FDA announcement that it would partially lift its embargo on PGS sales by allowing 23andMe to market its DTC carrier test for Bloom’s Disease. The FDA’s approval was based on 23andMe studies of the accuracy of its test for predicting Bloom Disease carrier status, and on surveys demonstrating that the general public was capable of following sample collection instructions and understanding test results.

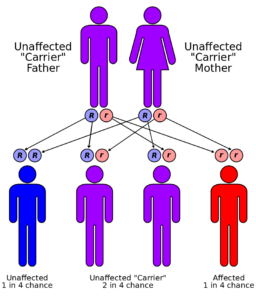

23andMe’s Bloom carrier test only assessed whether a healthy person had a variant in a gene that could lead to his offspring inheriting the disorder – that is, whether the individual was a carrier of the disease. It did not include information on the predisposition of that individual for developing the disease himself. By October 2015, 23andMe had gained FDA approval for an additional 35 carrier status tests.

23andMe’s front door was open for business again.

According to Alberto Gutierrez, Ph.D., director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, “The FDA believes that in many circumstances it is not necessary for consumers to go through a licensed practitioner to have direct access to their personal genetic information. Today’s authorization and accompanying classification [as a Class II device], along with FDA’s intent to exempt these devices from FDA premarket review, supports innovation and will ultimately benefit consumers.”

In April 2017, 23andMe obtained approval for Personal Genome Service Genetic Health Risk (GHR) tests for 10 diseases or conditions, including Parkinson’s Disease and late onset Alzheimer’s Disease. According to the FDA’s press release:

These are the first direct-to-consumer (DTC) tests authorized by the FDA that provide information on an individual’s genetic predisposition to certain medical diseases or conditions, which may help to make decisions about lifestyle choices or to inform discussions with a health care professional.

“Consumers can now have direct access to certain genetic risk information,” said Jeffrey Shuren, M.D., director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “But it is important that people understand that genetic risk is just one piece of the bigger puzzle, it does not mean they will or won’t ultimately develop a disease.”

Translation: While 23andMe tests are not exempt from general controls such as labeling requirements and manufacture under a quality assurance program, the company can market its products direct to the consumer without premarket approval or notification. In other words, responsibility for understanding the meaning of test results has shifted to the consumer. Even so, note the absence of a gold standard that the consumer can reference to determine clinical significance, often based on complex statistical, genetic, and biological analysis. In other words, once you have your test results, you are on your own – unless you choose to consult a medical professional. Even though the FDA’s approval ruled in favor of direct-to-consumer testing results going directly-to-the-consumer, it did not circumvent the medical industry entirely, implying a role for medical advice and genetic counseling on the back end, after test results were in consumer hands.

Just as the General Mining Act of 1872 resolved the dispute between the government and the mining industry, releasing miners and mining companies from the threat of federal ownership and control, the FDA’s recent approval of 23andMe carrier and predisposition tests released the DTC DNA testing industry from the threat of government control, and eliminated the role of the medical industry as a go-between with the consumer.

*****

Over a decade since 23adMe came on the scene, the company has developed some fierce competition. Ancestry.com began offering autosomal SNP tests in 2012; as of April 2017 it boasts a database of over 4M. More recently, in November 2016, fellow genealogy giant MyHeritage started its own DTC testing service. Although Ancestry and MyHeritage market autosomal testing solely for genealogical purposes, their terms of service and informed consent agreements are similar to those of 23andMe, indicating their interest in selling data through their back door to as yet unidentified organizations. While Ancestry and MyHeritage do not seem to have an interest in partnering with the pharmaceutical industry, their sales must have an impact on the growth of 23andMe’s customer database, and therefore 23andMe’s back door revenue stream. Even so, in early 2017, 23andMe announced its database had crossed the 2M mark.

Having so much data to work with is exciting for genealogists engaged in birth parent searches and to the average consumer interested in discovering his genetic tendencies and ethnic background for $100-$200.

Consider, however, the bigger picture.

The world has changed. We now live in a data-harvesting universe, where everything from the car we drive to the clothes we wear to the food we eat is monitored and tallied by marketing companies for sale to who knows whom. By the way, did you know that the first organization to know there is a flu outbreak is not the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta. It’s Google.

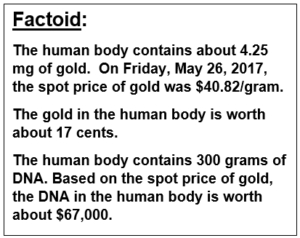

For about $100, a consumer is presented with a list of autosomal matches (“DNA-cousins), information about his ethno-ancestry, and, in the case of 23andMe, his carrier status and estimates of his predisposition to genetic disorders. For perhaps $10M, a medical research group is presented with that same data anonymized and consolidated with tens of thousands – if not a million – sets of test results to use for drug development. The amount of gold in the hills of California, or in the world for that matter, is finite. The amount of human DNA in the world and how that DNA can be repackaged is infinite. A nugget of gold can only be sold to one person at a time, but a genetic dataset can be mined in many ways and the analyses sold to more than one interested party, even as personal test results are given to the individual who paid for them.

So where are we going with all this? What does the future hold for the New Gold Rush?

Just as the billions of dollars of gold pulled from the ground during the California Gold Rush permanently changed the physical landscape of the Sierras, the DNA Gold Rush of today is changing our personal landscapes of privacy and informed consent. The gold in the hills of California may one day be exhausted; the supply of human DNA will never be. It is difficult to predict what the future holds for us, as both the consumer and the consumed.