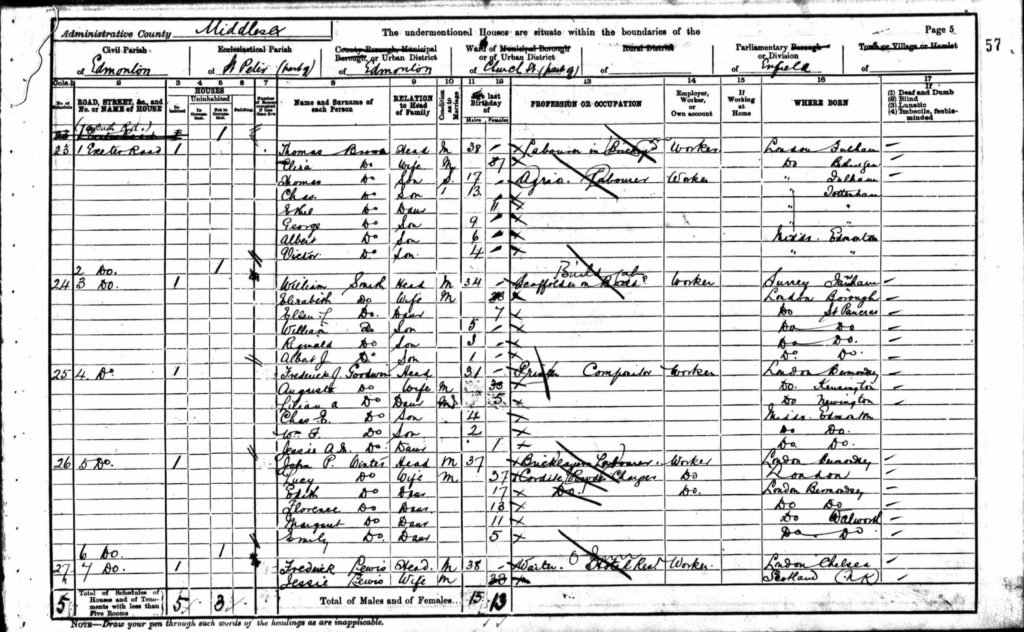

When AFDIL attempted an identification through Y-DNA, I was asked by my colleague Dr. Odile Loreille to find a Y-DNA reference for Sidney Goodwin. We were just finishing up the identification of The Hand in the Snow, so she knew I was available for a new project. Of course, my first step was to search Ancestry.com to obtain information about the Goodwin genealogy. I immediately found Sidney’s parents Frederick and Augusta in 1901 living in Middlesex with their four oldest children Lillian (5), Charles (4), William (2), and Jessie (1). Frederick was listed as a print compositer.

Because Frederick and his sons perished on the Titanic, to find a Y-reference for the family I researched Frederick’s three brothers to see if they had any living male descendants. Frederick’s older brother Thomas (b. 1869), emigrated to Niagara Falls, NY in the mid 1880’s. It was on Thomas’ suggestion that Frederick had decided to move with his family to the United States to work at a new power station opening in 1912. Unfortunately, Thomas had only two daughters.

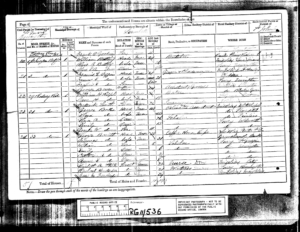

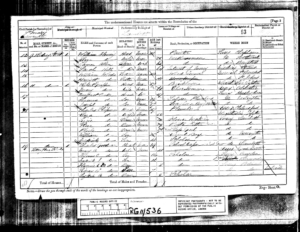

According to the 1881 Census, besdies Thomas, Frederick had two other brothers, Sidney, who was mentally retarded, and Frank, who never married. Since there were no living males descending from Frederick’s brothers, I researched Frederick’s paternal uncles for surviving male lines. Frederick’s father Charles had several brothers, including Samuel, b. 1838.

I was surprised to find a website dedicated to Samuel Goodwin and his family. The site had been posted by a genealogist named Margreet from the Netherlands, who had taken an interest in the Goodwin family story. Margreet was kind enough to put me in contact with Carol Goodwin, the matriarch of the Goodwin family, whose grandmother had been the sister of Frederick Goodwin. Carol had been working on a book Titanic’s Unknown Child about the Titanic Goodwins, and provided me with much valuable genealogical information about the family that was useful for tracing a family reference.

Margreet told me that about ten years earlier, she had been in touch with a Graeme Goodwin in Australia who was the grandson or the great grandson of Samuel Goodwin of the Titanic family, but she had lost contact with him after he changed his email address. Fortunately, she was able to remember his middle initial and that he lived in Queensland with his sister. This provided me with enough information to locate him. There were only two G. A. Goodwins in the Queensland telephone directory, and he was the second one I called. He confirmed that he was the Graeme Goodwin whose family members had been lost in the Titanic and who had been in touch with Mary years earlier. Graeme was delighted to be back in contact with his extended family.

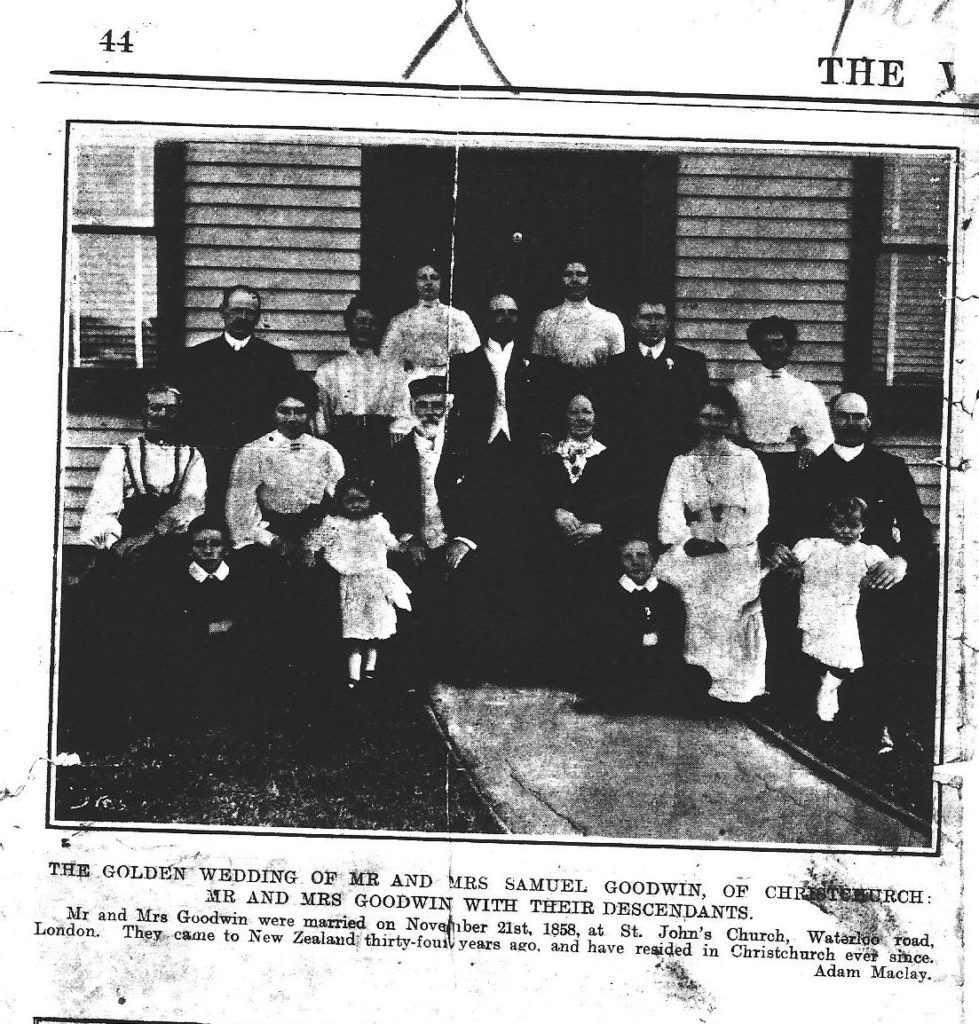

Graeme had a photograph of Samuel Goodwin and his family that was published in the newspaper in 1908 on the occasion of Samuel’s 50th wedding anniversary. The caption said the family lived in Christchurch, NZ. Graeme told me that Samuel had originally immigrated to New Zealand, but that his own branch of the family had moved to Australia more recently. Samuel’s picture helped me locate a second Goodwin living in Dunedin, NZ as a backup. Because there is a chance of an unrecorded adoption, name change, or illegitimacy in a family, it’s good to have two DNA references for an identification.

Meanwhile back at AFDIL, Dr. Rebecca Just, Dr. Odile Loreille and their team of researchers made an attempt to distinguish the two children using the mtDNA coding region, since analysis of the HVR1 and HVR2 control regions had failed. They used two commercially available SNP assays that had proven useful in differentiating HV haplotypes. Yet the coding region results of the Panula and Goodwin families references were identical.

As a last hope, the team used a more targeted approach, studying 92 published mtDNA genomes with the HV haplotype, searching for regions that had high levels of inter-individual variation. They discovered a region bounded by positions 8,164 and 11,160 that had not been covered by the two standard SNP assays. In this region, they discovered a rare mutation at position 9923 that the Goodwin reference had, but that the Panula reference lacked.

The remains also exhibited this rare mutation. The tie was finally broken. The Goodwin reference matched the remains in HVR1, HVR2, and in the coding region. The Panula reference had one mismatch in HVR2, and a second mismatch in the coding region at position 9923, giving the two differences required by forensic guidelines for a rule-out. After 90 years, the Unknown Child on the Titanic finally had a name. He was Sidney Leslie Goodwin.

Epilogue

In August 2008, led by matriarch Carol Goodwin, the Goodwin family met in Halifax for a memorial service to honor Sidney and the other 52 children who died on the Titanic. Goodwin family members came from California, Wisconsin, New York, and England to attend the ceremony. I was invited to attend as I had been made an honorary member of the family.

Sidney’s memorial service was held at St. George’s Anglican Church, where the Unknown Child’s funeral had taken place in 1912. The family assembled at Sidney’s grave in Fairview Lawn Cemetery, where the service was continued. A bell was rung as the name of each child who died was read by members of the family.

Our Goodwins also visited the Martime Museum of the Atlantic, where one by one each of us was allowed to hold the tiny shoes that had provided the key to reversing what could have been a serious historical error that would have gone tragically uncorrected.

I was allowed to hold the childs shoes.

*****

In 1911-1912, a pair of small brown shoes was manufactured somewhere in England. It made its way to a retail shop where Augusta Goodwin bought them for her baby son Sidney to wear on the family’s journey across the Atlantic where her husband Frederick had the promise of a new job in America.

Sidney would die wearing those shoes a few short months later, along with Augusta, Frederick, and their other five children: Lillian (16), Charles (14), William (11), Jessie (10), and Harold (9) , victims of the worst maritime disaster in history. They might not have perished if the politics of the times had been different. The family had booked third class passage on a small steamer out of Southampton, but due to the coal strike that year, the voyage was cancelled and the family was transferred to the Titanic.

Ninety years later, the ordinary little shoes that Sidney wore the night he died would become an extraordinary key to one of the most compelling stories of human identification.

Yet even more important than his shoes, was the blueprint Sidney carried in each cell of his body that defined who he was-the blueprint called DNA. It would take decades before DNA identification would be discovered, even as Sidney’s remains were dissolving into the soil where he was laid to rest in 1912. It would take even more years for DNA analysis to mature into a sophisticated science that had a chance of identifying Sidney’s remains, and by that time only crowns of three of his milk teeth and a small bone shard would be left. And even as the small amount of DNA that could be extracted from one of those crowns and from the bone was consumed in multiple rounds of testing, it would take the stubborn persistance of ancient DNA specialists and scores of genealogists from around the world to finally identify him based on only one picogram of DNA – about the amount of DNA present in only a single cell of his body.

And now, even that is gone.

20 Responses

HI,

My great- great grandpa was Arthur Lawrence Goodwin married to Mabel Goodwin. Arthur’s father was Joseph Richard Goodwin. We were told by Arthur’s daughter Ivy Mabel Goodwin that we had relatives that died on the Titanic. We are just inquiring to find out if we are related to this Goodwin Family. Please put us in contact with Carol.

Thanks!

Hi Amanda,

I will be glad to. I will write you directly and give you Carol’s email address. Her book on the family has just been published. She would know how to connect you in better than anyone else.

Colleen

i think i might be related in some way when my mother died i found a card from titanic saying sorry for you lost