Sarah Yarborough Case

The 1991 Murder Of A 16-Year-Old High School Student Touched The Entire Community. It Was Also The First Case Ever To Use Genetic Genealogy.

Sarah Yarborough’s yearbook

photograph, 1991

“Although We Went On With Our Lives, It Was Always In The Back Of Our Minds As Unfinished Business. In A Way It Was Damocles’ Sword Hanging Over Us. We Never Knew When, Or If, The News Would Come But We Knew When And If It Did, All The Emotions Would Come Roiling Back And We’d Be Thrown Into 1991 Again. To Live With That For 28 Years Is Exhausting. If It Had Never Been Solved, It Would Have Been A Shadow Over Us The Rest Of Our Lives.”

Laura Yarborough, Sarah’s Mother

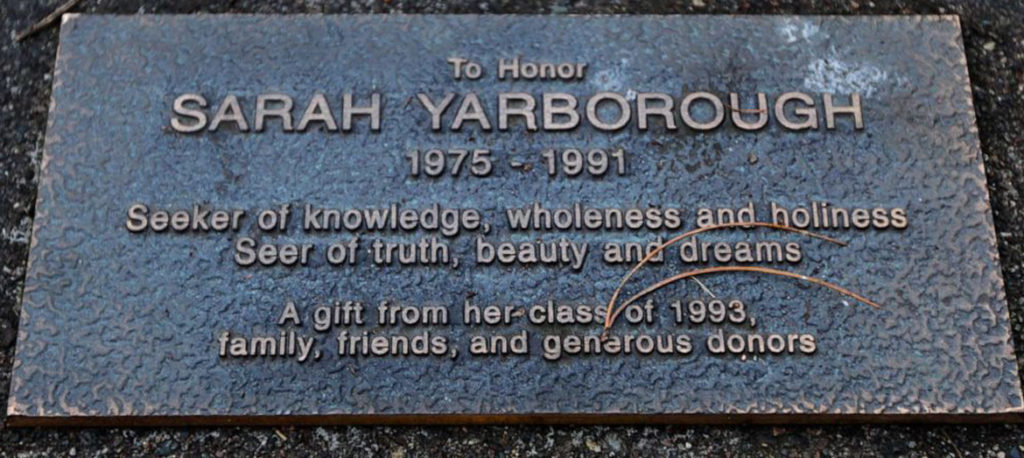

A memorial plaque erected to honor the memory of Sarah Yarborough. (Ted S. Warren/AP photo)

“Dna Has Linked The Suspect All The Way Back To The Family Of Robert Fuller, Who Was Related To Two People Who Came To The U.S. On The Mayflower. Unfortunately For Law Enforcement Officials, Fuller First Settled In Salem, Mass., In 1630. With No Forwarding Address To Work From, The Latest Information Does At Least Give Police A New Starting Point…”

Tim Newcomb, Time – Jan. 11, 2012

The pioneering use of genetic genealogy in 2011 to generate forensic intelligence on the 1991 Sarah Yarborough homicide was an inauspicious start to what has become a revolution in human identification. The Yarborough homicide was the first known instance where direct-to consumer (DTC) DNA test data was used to generate investigative leads for a cold case, opening the door for countless others that have since been solved using genetic genealogy. The case presented unexpected twists, including a link between Sarah’s killer and passengers on the Mayflower.

A world-class effort goes cold

Sarah Yarborough was the all-American girl next door. Her murder frustrated King County law enforcement for nearly 30 years and deeply affected the tight knit community of Federal Way, Washington.

The community banded together to build a memorial in her honor which still stands today at Federal Way High School. Sarah’s grandfather facilitated the donation of a state-of-the-art computer system so that the thousands of tips pouring in could be organized and tracked by law enforcement.

Washington State Patrol Crime Lab DNA scientist Jodi Sass was a new DNA analyst in 1991 who worked tirelessly on the case. Anytime a new suspect sample was obtained she rushed the results, to no avail. The investigators, scientists and media kept the case alive over the years. Nobody was going to give up on finding justice for Sarah.

Everyone involved in investigating her murder felt a deep sense of responsibility to solve her case. Detective Jim Doyon took over the case early on. The well-respected homicide investigator was a legend in the sheriff’s department and part of the Green River Killer task force. As time passed without a suspect being identified, the stark reality began to sink in that this was not going to be an easy case to solve.

The case had all of the solvability factors that investigators could ask for: a single source male profile; two eyewitnesses who provided a sketch along with a detailed description of the suspect. Tremendous media attention generated thousands of leads. The Washington State Police Crime Laboratory routinely ran the profile in state and national CODIS databases. It was also run through Interpol. Between 200-300 hundred individuals were swabbed, yet no suspect was identified.

And the case went cold.

Connection to the Mayflower

In 2011, when Identifinders first began working the case, a match was found for the killer’s Y-STR profile to members of the Fuller Y-STR surname project. This project’s participants were descendants of Robert Fuller of Salem, Massachusetts in the 1630s, a relative of the Mayflower Fullers. Suspicion fell on William Fuller, a long time Yarborough family friend, who had been in the area at the time of the murder, and whose daughter Elizabeth was Yarborough’s classmate.

When William Fuller voluntarily gave a DNA sample, it was determined that he was not the killer nor was he the father of the killer. However, his Y-STR profile matched the Y-profile from crime scene DNA, indicating he was a paternal cousin of the killer. Although it was not possible to estimate how closely they were related, the unusual situation developed that although the killer was still unknown, authorities knew his genealogy back to the 1600s.

This generated tremendous press at the time, even making TIME.

Other Fullers living in the area were investigated but the case went cold again.

Filling Loopholes

The Yarborough homicide was first attempted in 2011 by comparing the Y-STR profile obtained from crime scene DNA to public Y-STR genetic genealogy databases. When the case was solved in 2019 using autosomal SNP testing, it was discovered that Sarah’s killer could have been identified at least twenty years earlier through CODIS, but loopholes in the legal system had allowed him to avoid detection.

The 2019 identification of Patrick Nicholas as a suspect using autosomal SNP testing raised awareness of the limitations of CODIS, and fueled debate over the role of familial searching versus forensic genetic genealogy. Nicholas was convicted in 1983 of attempted first-degree rape in Benton County, WA before CODIS was launched in the 1990s. In 1993, he was arrested again for first degree child molestation. Although his DNA profile should have been entered into CODIS, he was allowed to plead to gross misdemeanor that did not require DNA collection. He escaped detection a second time. After Nicholas ’arrest, it was discovered that his brother Edward had already been entered into CODIS for a prior conviction for rape in the first degree; he was also a registered sex offender. Because Washington does not practice familial searching, Patrick Nicholas had escaped detection a third time.

Upon Nicholas’s identification using genetic genealogy, King County Sheriff’s Office quickly secured his DNA from discarded cigarettes. His DNA was found to be a CODIS match to the DNA profile developed from the victim. Nicholas has been charged with first degree murder with sexual motivation. He is currently pending trial in King County Superior Court, Seattle, Washington.

Although the case became one of the first to use autosomal SNP testing in 2014, the type of SNP analysis that was available to the forensic community at that time was primitive compared to the Direct-to Consumer (DTC) genealogical techniques used today, so it did not prove very useful.

By 2019 however, genetic genealogy had finally advanced and succeeded where the legal system had failed. The perpetrator, identified as Patrick Leon Nicholas, had escaped CODIS identification three times, thanks to loopholes in the legal system. Ironically, since Sarah’s killer was named Nicholas and not Fuller, it also pointed out the

limitations and need for judicious use of all tools, including Y-STR analysis.

His grandfather was adopted. This meant that his legal surname was not his biological surname, highlighting the fact that even genetic genealogy has its loopholes.

The cold case solves that appear in the headlines today may be exciting news, but they are the product of a slow and steady development of the forensic use of genetic genealogy. And it all started with a young woman named Sarah.

Identifinders Case Team

Their work on this case merited 5th place in the Gordon Thomas Honeywell 2020 Cold Case Hit of the Year contest out of 50 entries from 20 countries.

Colleen Fitzpatrick

Gretchen Stack

Holly Turk